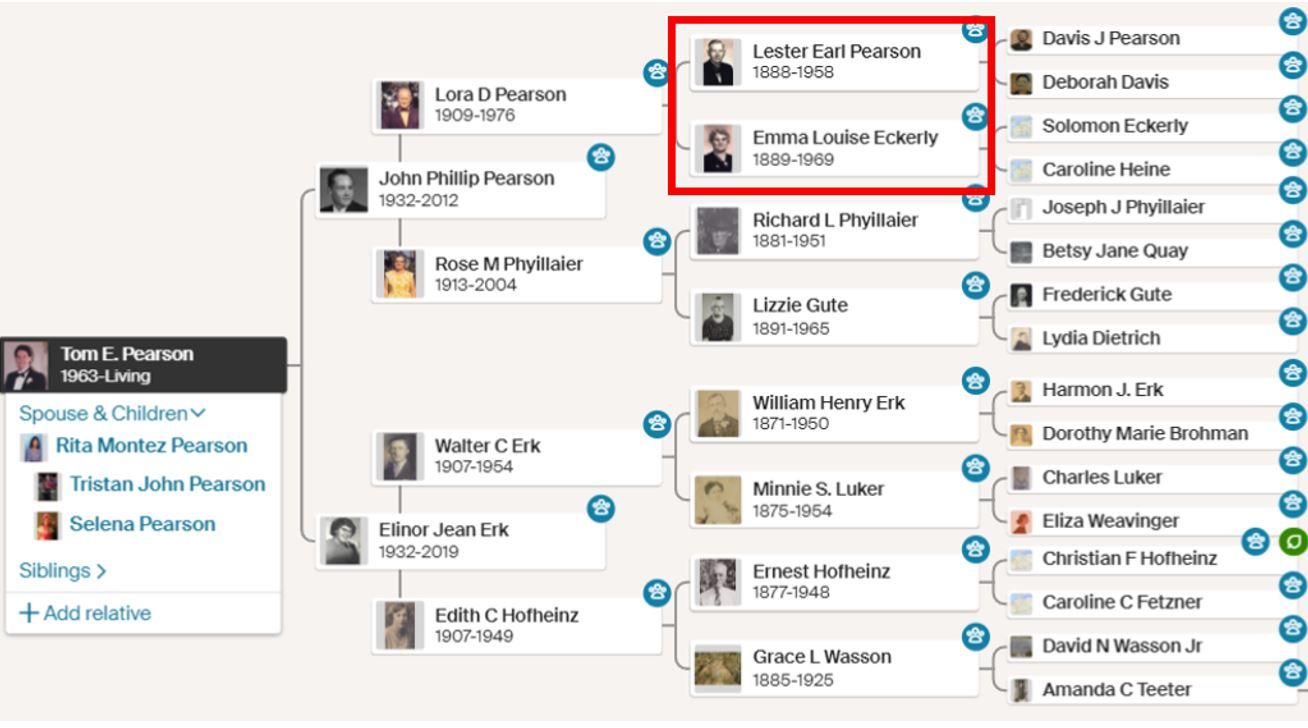

Author: Tom E. Pearson

Email: tepster1@gmail.com

Published: Aug. 2022

Preface:

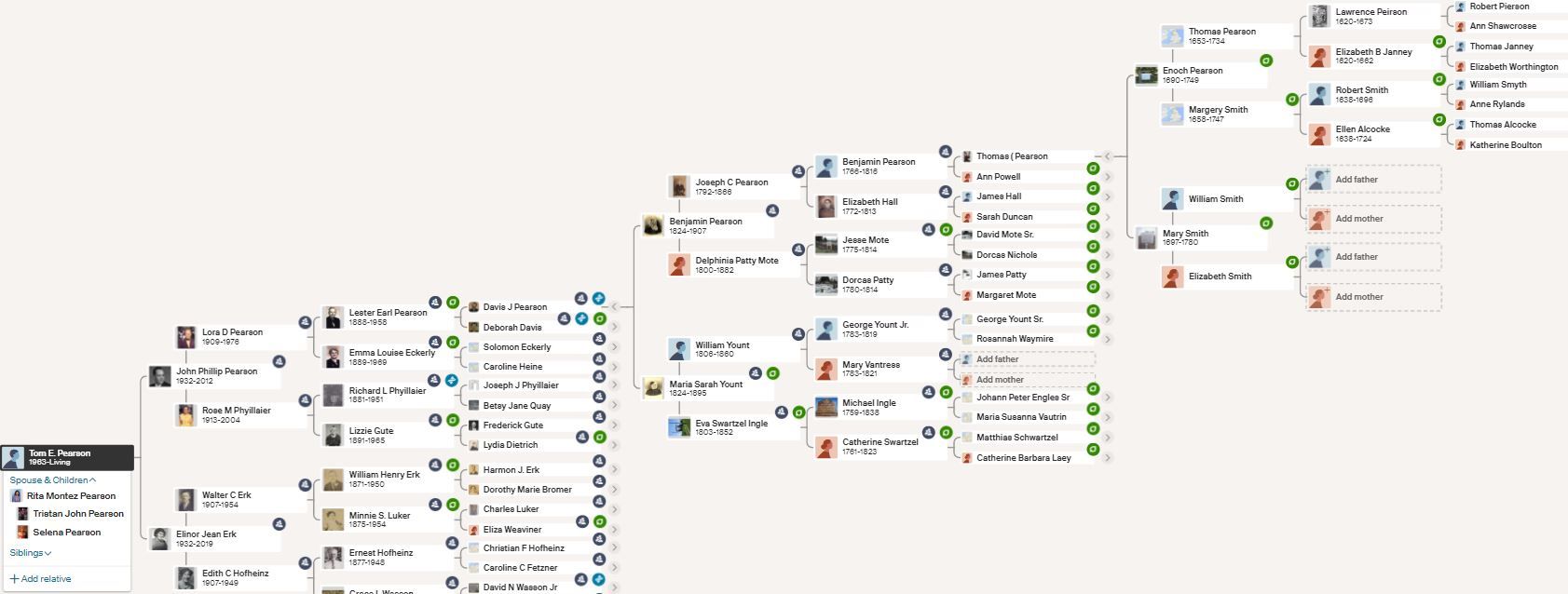

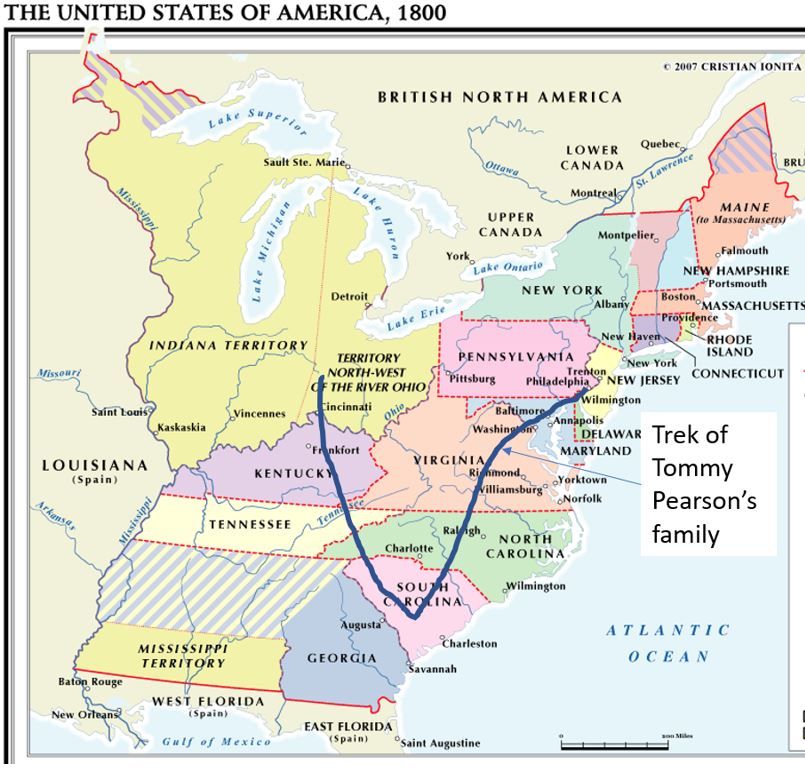

This story weaves the lives of my ancestors into the tapestry of their surrounding environment and the historical times they lived. It begins its captivating journey in the aftermath of the last ice age, around 10,000 BC, exploring the dawn of prehistoric times. From there, it propels us forward to the emergence of our first documented ancestors in Wilmslow, England. We then embark on a riveting narrative that follows the footsteps of my ancestors as they venture across the ocean to America in 1683, forging a new path in the unfamiliar land. The narrative takes a southern turn, leading us to Bush Creek, South Carolina, before ultimately leading us to the dark forest of the Ohio Miami Valley. To facilitate the reader's connection with my paternal direct ancestors, their names are highlighted in bold throughout the book.

I would like to thank the people who have helped with the information in this book as no ancestorial history done well has only one author.

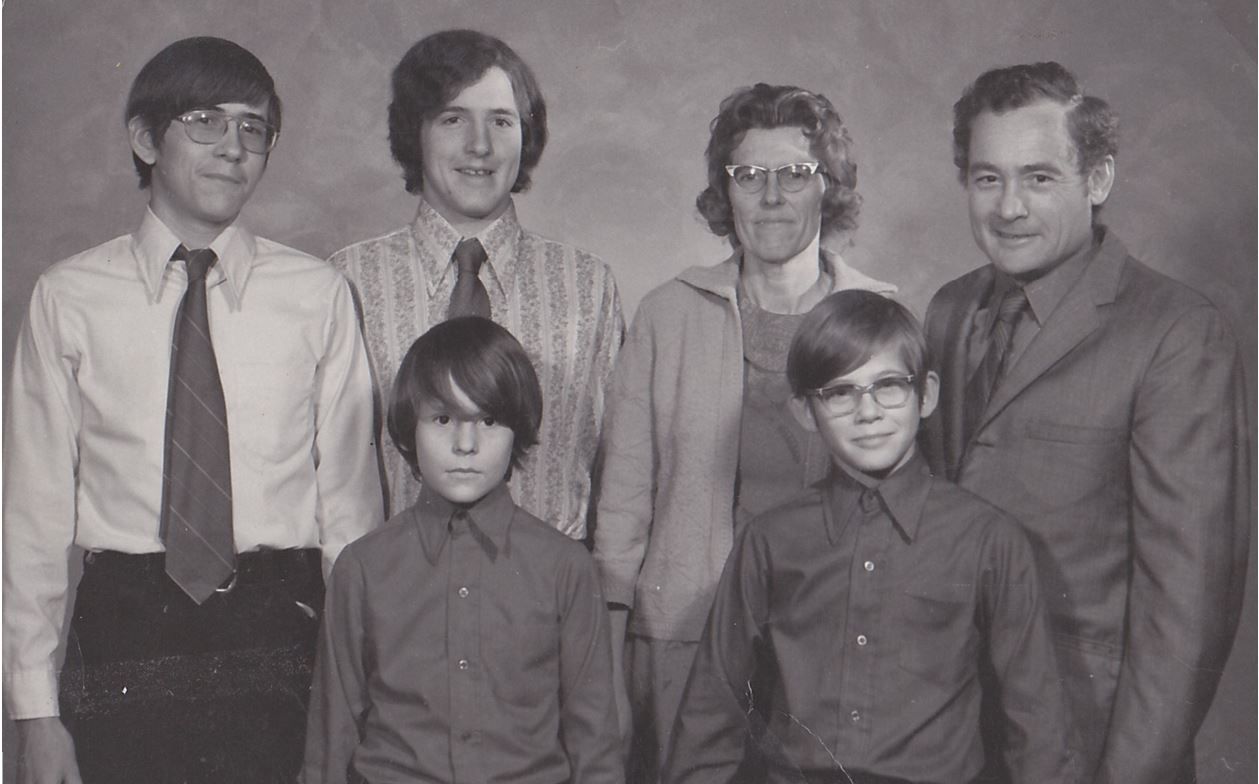

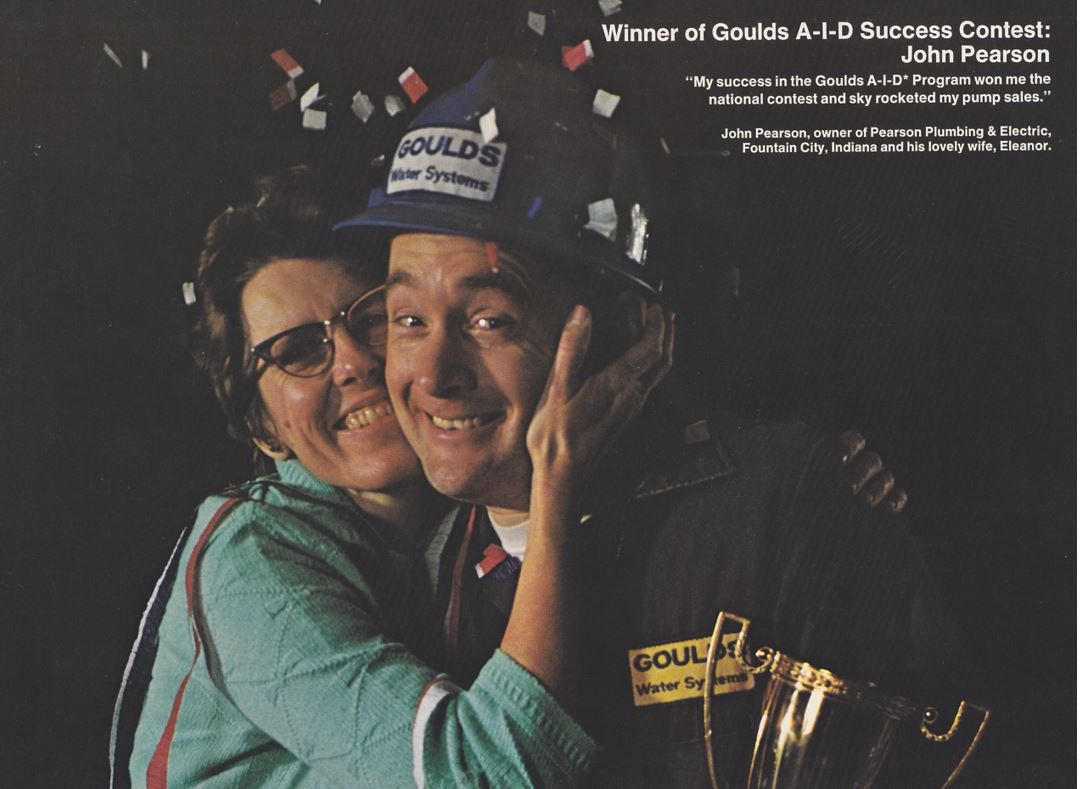

- Thank you to my father John Pearson (b1932) for starting me on this genealogical journey of our family with his first book "Quaker Pearson" by Dependable John Pearson written in 1992.

- Special thanks to Steve Pearson for his ancestry information, Y-DNA research, and Pearson Facebook page that has connected me to my other relatives. It was an unexpected breakthrough finding Steve as my 7th cousin in 2014 through FTDNA that validates our paternal Q-L807 DNA as a Pearson paternal DNA marker.

- Thanks to Paul C. Palmer for his extensive research into Robert Pierson (b1580) and providing a better alternative to Lawrence's Pierson's (b1620) father.

Chapter 1

Wilmslow, Cheshire England - where the records of my ancestors begins

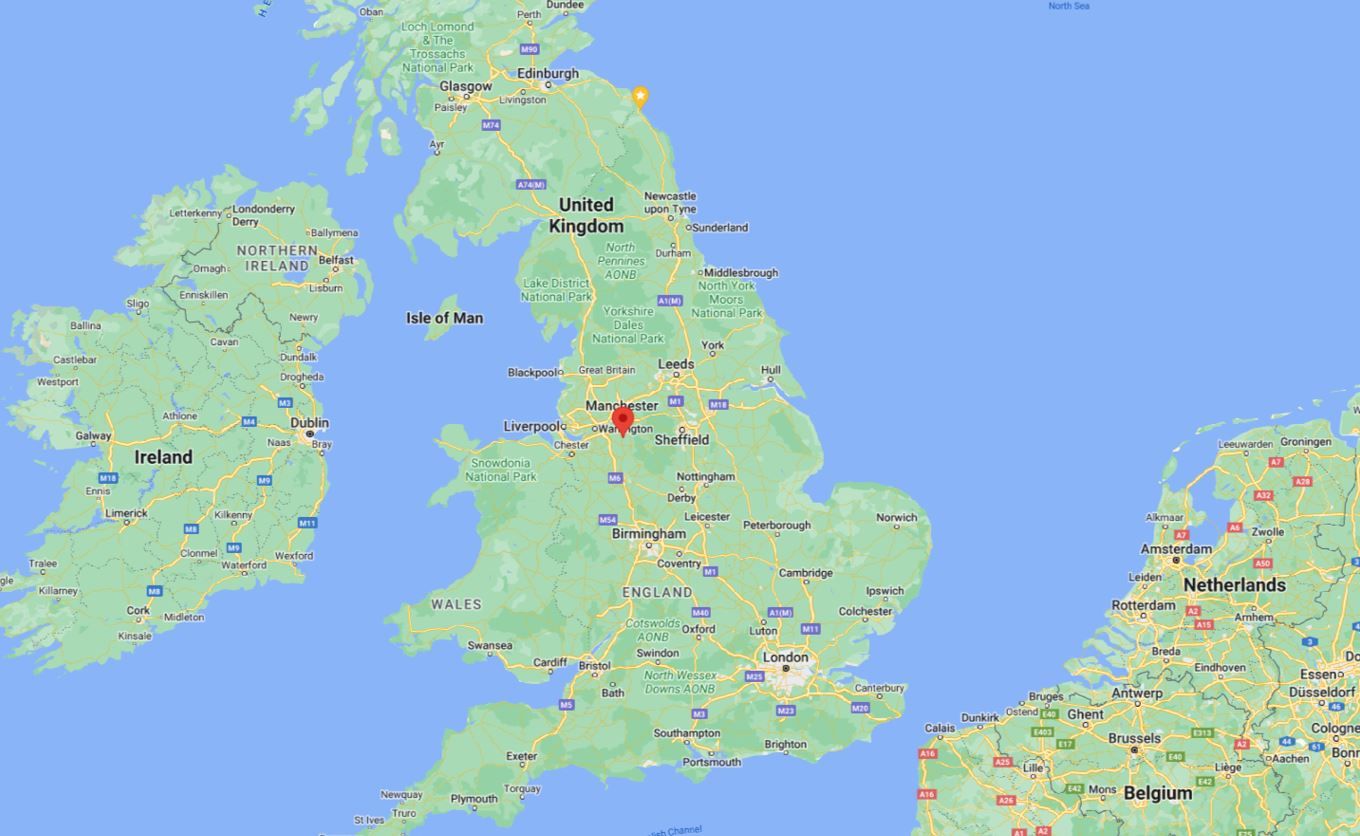

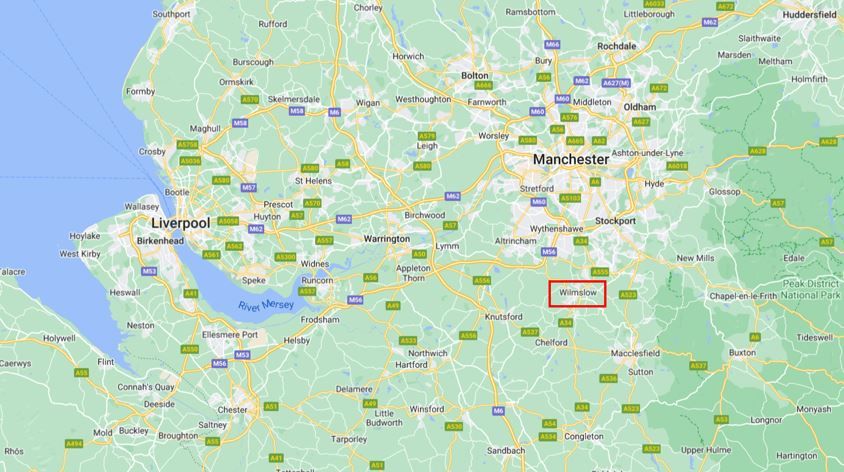

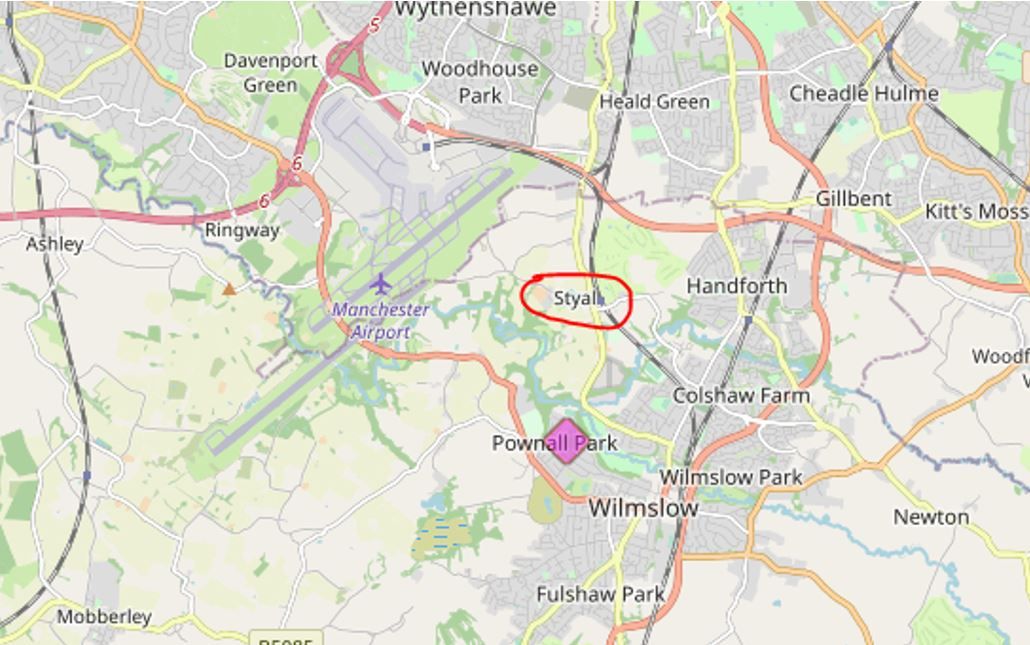

Wilmslow, situated in Cheshire County, England, is a captivating village encompassing a parish and townships. It rests peacefully along the banks of the river Bollin, approximately 11 miles to the south of today's bustling Manchester downtown. Within its borders lie the townships of Bollin-Fee, Chorley, Fulshaw, and Pownall Fee, which served as the home and workplace for Lawrence Pierson (b1620) and his family. St. Bartholomew's Church played a vital role in catering to the spiritual needs of the residents of Pownall-Fee and Bollin Fee townships. Pownall-Fee further comprises the charming hamlets of Morley, Styall, and Stanilands, extending across an expansive 3,556 acres, positioned about 2 miles northwest of Wilmslow.

During the 1881 census, the Pearson surname ranked as the fourth most common in Pownall Fee, Cheshire, suggesting the likelihood of numerous distant cousins still residing in the vicinity. While the earliest documented record of a church in Wilmslow dates back to 1246 AD, it was a modest nave that graced the landscape. Subsequently, the lower section of the tower was created in the 15th century, and in the early 16th century the church witnessed an additional expansion. Presently, Wilmslow thrives as a town located 11 miles south of Manchester, deriving its name from an Anglo-Saxon origin, signifying "mound of a man called Wighelm."

Figure 1.1 – Wilmslow, England located at the red pin is 11 miles south of Manchester and neighbors the current day Manchester airport.

Pownall Fee of Cheshire

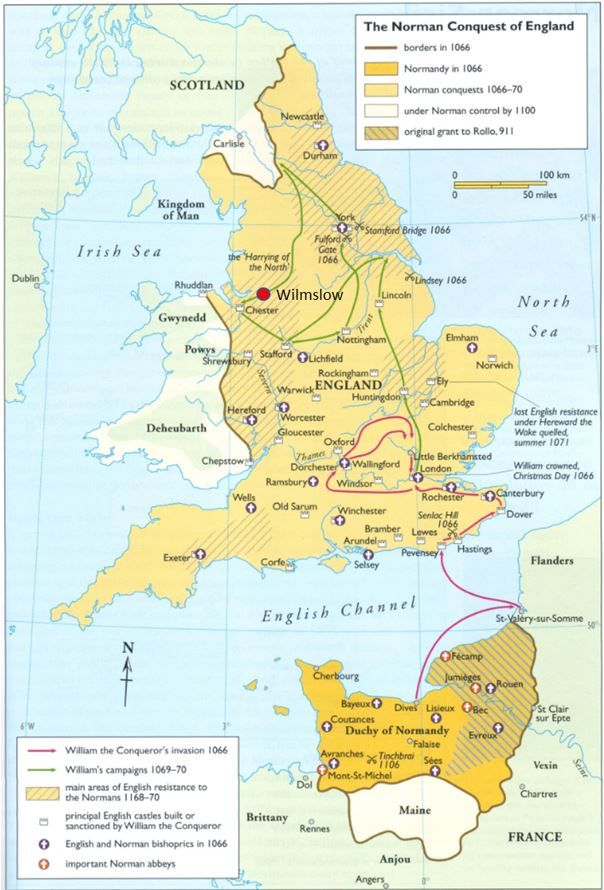

Pownall is among the myriad of surnames that emerged in England as a result of the historic Norman Conquest in 1066 AD. The Pownell family held the esteemed title of lords and landowners, while our Pearson ancestors served as tenants, diligently cultivating the land. In recognition of their distinguished contributions during the decisive Battle of Hastings, the Pownells were bestowed with lands from the spoils of war by Duke William of Normandy.

Fig 1.2 - Map of Cheshire England 1577 AD. Yellow highlights Pownall in relationship to the small village of Wilmslow

Fig 1.3 - Today’s map and location of Wilmslow just south of Manchester England.

Cheshire, England

Chester, a word of Saxon origin, carries the meaning of a fortified or defended site. The term "shire" denotes the county of Chester. Therefore, Cheshire is an English county encompassing the city of Chester. It was in Chester that William the Conqueror erected a castle upon the remains of the village he had destroyed, thus establishing Chester as the feudal capital.

Following the clearance of forests by the early settlers, Cheshire transformed into a bountiful farming paradise. Its expansive, fertile valleys and consistently damp climate proved ideal for livestock grazing, surpassing the cultivation of crops. The abundant grasslands provided excellent sustenance for sheep and cattle, thriving well into the autumn season. Cheshire is excellent grazing county with topsoil consisting of clay and lime providing rich soil that grew the grass that fed the cattle and sheep.

Prehistoric Cheshire, England

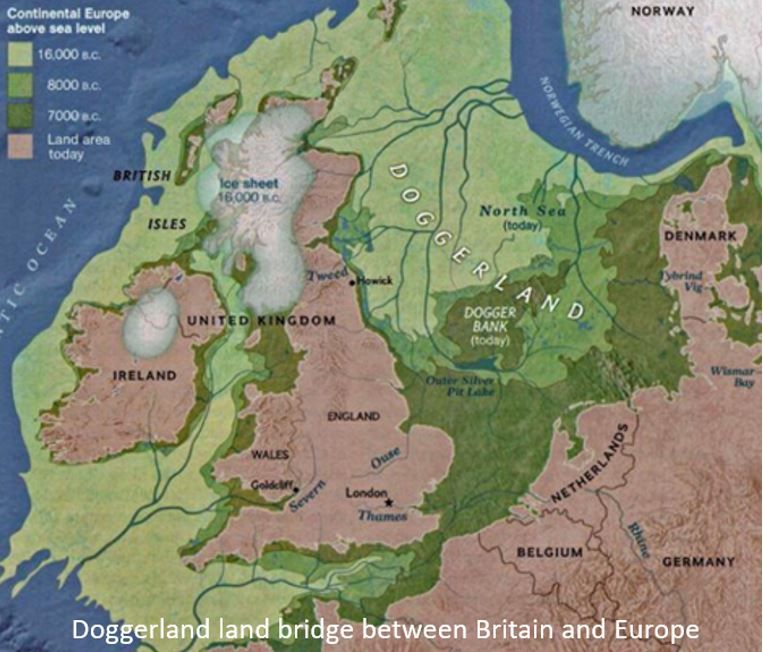

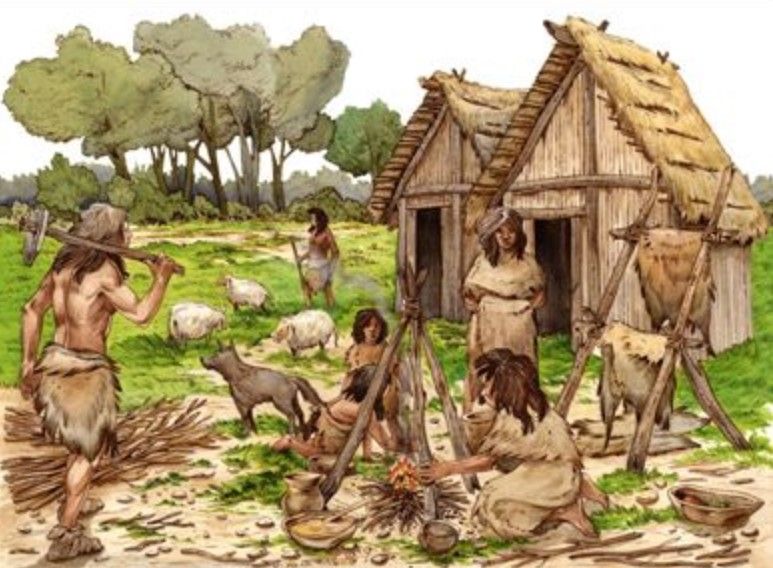

After the last ice age approximately 10,000 years ago the glaciers that once covered Cheshire gradually receded allowing the sea level to rise along with a new breed of hunter-gatherers that migrated into Cheshire from the south of England. When they arrived, they found old-growth oak wood forests with a variety of animals. The woods thrived with deer, wild boar, and fowl on the lakes, ponds and sea surrounding the area. Trout was also in large quantities in the rivers providing a rich protein diet that fed the growing evolving brains essential for competitive survival and became part of their culture and religious practices by sacrificing animals to appease their gods.

Around 5,000 BC sea levels increased 300 feet and the land bridge called Doggerland that is between Europe and Britain submerged into the North Sea creating the islands of England and Ireland. Over next few thousand years and until now, the animals and our ancestors were locked into symbiotic relationship in a co-evolution that started with hunting and then progressed into domestication of animals where new varieties of animals emerged that met the needs of our ancestors.

Around 3,000 BC, our hunter-gatherer ancestors embarked on a transformative journey as they transitioned into settled communities. They began clearing patches of forest to cultivate the land and ventured into animal husbandry. Farmers across various regions engaged in the selective breeding and domestication of animals, such as dogs, cats, sheep, goats, hogs, cattle, and fowl. These animals not only provided sustenance but also contributed to various aspects of settlement life, including transportation, labor, cavalry, and pest control.

The domestication of animals is a process shaped by "natural selection" influenced by humans. As our ancestors formed communities, animals that displayed resistance to domestication were not able to thrive. Wild animals, known for their disruptive behavior, were driven away from the settlements through hunting. In contrast, tame animals were protected and encouraged to breed. Over time, with predators eliminated, our ancestors witnessed the evolution of docile and robust cattle, yielding plentiful milk, and sheep boasting shaggy fleeces that enlivened the land.

The intentional shaping of animals by humans was mirrored in the cultivation of crops, which included grains, vegetables, and fruits. Careful selection was employed to enhance yield and nutritional value. With the clearing of forests, draining of marshes, fortification of hills, and bridging of rivers, the foundations of civilization were laid. Houses were built, graves were dug, and the landscape underwent significant changes as clay fields were plowed, hay was harvested, roads were worn, fields were enclosed, streams were dammed, and swamps were drained. The countryside itself took on a new shape, shaped by the efforts of humanity.

Over the vast expanse of time, the selective breeding of animals was accompanied by the selective breeding of our ancestors. It is conceivable that traits such as larger brains and lactose tolerance might not have become advantageous survival traits without the domestication of animals. Thus, a symbolic relationship of evolution emerged, where cattle became products of human intervention, and our ancestors evolved to become smarter and better equipped for survival due to their association with cattle.

Our Cheshire ancestors' behaviors adapted to their surroundings, fostering the growth of civilization. Social teamwork, food sharing, trade, laws, and technology flourished, nourished by the cooperative cultural behaviors inherited from our ancestors. These behaviors also shaped their development of empathy, language, property ownership, and trade, guided by generally accepted systems of rules and laws. Our ancestors thrived and prospered because of their relationship with cattle, and in turn, cattle prospered because of our ancestors.

Bronze Age - 2500-750BC

Now, let's delve into the identities of our Cheshire ancestors. Prior to the arrival of the Romans from the south, the region was characterized by its inaccessibility, challenging travel conditions, and sparse population. Situated twenty miles to the southwest of Wilmslow, Eddisbury Hill fort stands as one of the earliest known settlements in the area, dating back to the Bronze Age. This community brought with them the knowledge and skill of refining metal, introducing this craft to Great Britain.

Our ancestors discovered the remarkable potential of mixing copper with a small quantity of tin, resulting in the creation of bronze—a metal alloy significantly harder than pure copper. This breakthrough gradually supplanted stone as the primary material used for crafting tools and weapons. The Bronze Age, a period lasting approximately 1700 years, witnessed the prominence and utilization of this innovative metal alloy.

Iron Age – 750 BC–Romans

The Celtic influence in Cheshire arrived relatively late, but eventually, a tribal group established itself in the region, known as the Cornovii tribe. It was this group that began to shape and transform the Cheshire landscape. The industrious efforts of these early farmers, along with their domesticated animals, led to the clearance of land, the nurturing of meadows, and the creation of pathways that later evolved into roads.

In addition to agricultural surpluses, early trade in Cheshire encompassed the valuable commodity of salt. This mineral was traded along ancient salt routes to neighboring communities and even beyond, serving as a significant source of commerce and exchange.

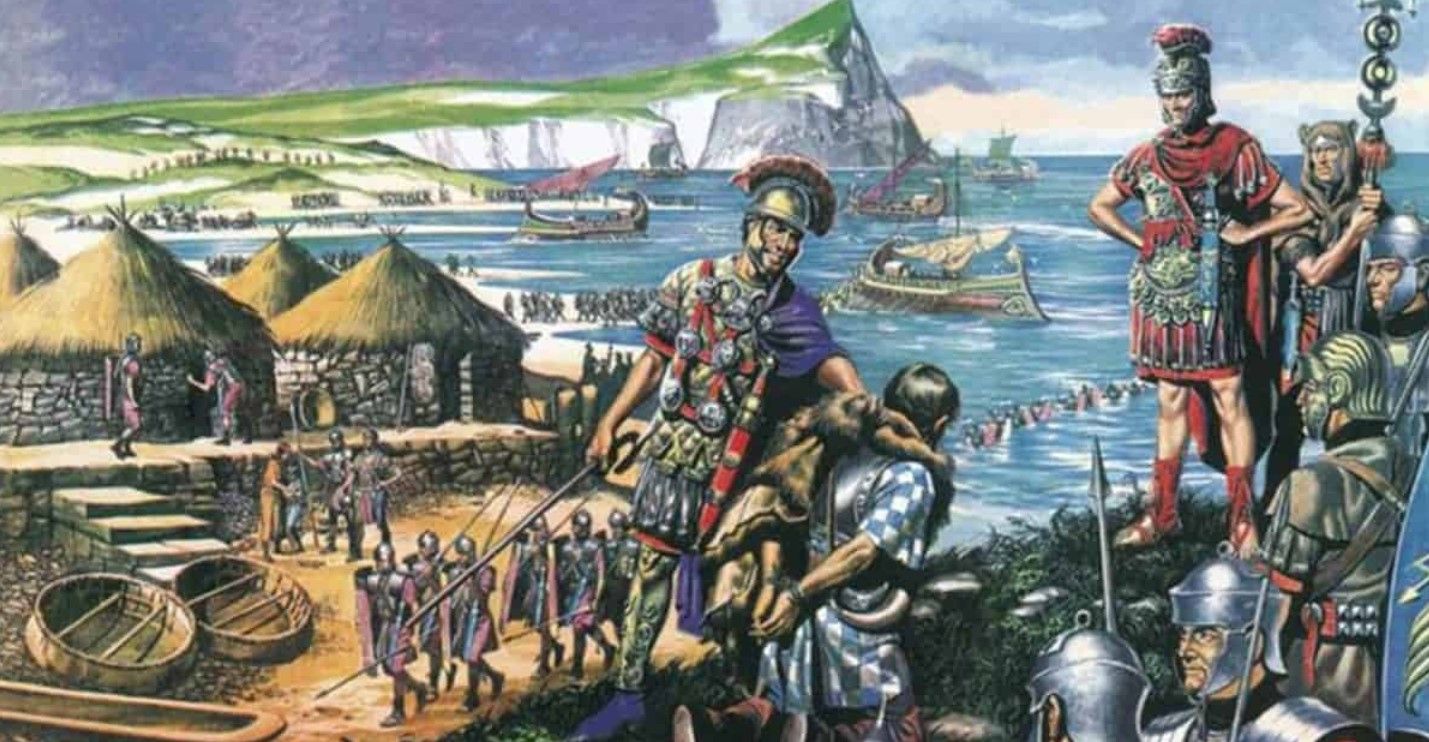

Romans - 55 BC- 380AD

Upon the arrival of the Romans, they encountered Celtic tribes in Cheshire who boasted agricultural surpluses, organized defense systems, and engaged in trade involving metals and salt. However, unlike their counterparts in southern England, the Cornovii tribe in Cheshire offered little resistance to the Roman invasion. Perhaps they had heard of the fate suffered by the wealthier tribes in the south and realized their own vulnerability due to their smaller numbers and scattered settlements.

The exploitation of Cheshire's salt resources, coupled with an established distribution network, brought the Cornovii tribe a degree of wealth. This prosperity was further augmented through cattle breeding, herding, and trading. However, from around 200 AD, the city of Chester began to experience a gradual decline, and with it, the supporting trade networks, markets, and administrative structures established by the Romans. Internal conflicts within the Roman Empire, attacks from barbarian forces along extensive borders, and diminishing returns from land and taxation made it increasingly challenging to maintain a standing army stationed in Chester.

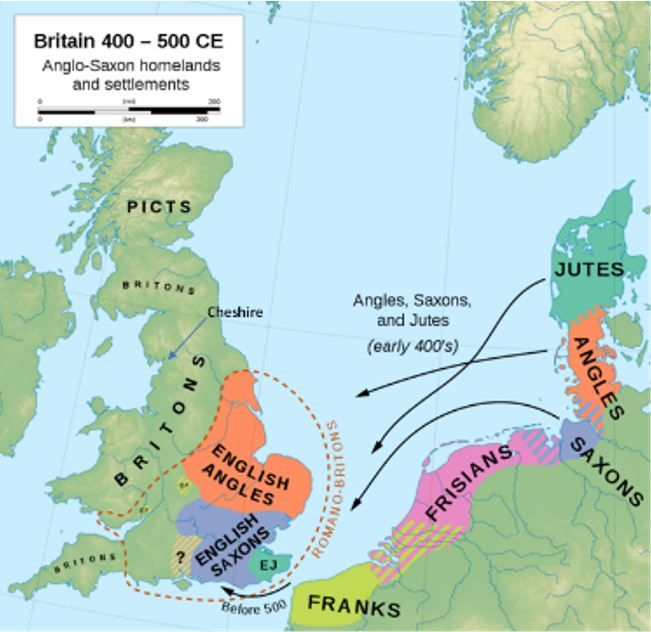

As a result, the Romans eventually withdrew from Chester around 380 AD, and Cheshire returned to an economy that operated in relative isolation, beyond the direct influence and attention of most towns in southern England, except for its significant salt trade. The map below illustrates that Chester, along with the majority of northern and western England, was inhabited by the Britons, while the Angle and Saxon populations resided in the south, near present-day London.

The foundation of English society was established through a bottom-up approach, gradually evolving over centuries through the efforts of local farmers, warriors, and their churches. Within this framework, the English Bishops emerged within the church hierarchy, assuming responsibility for spiritual matters and taking the lead in promoting the social behaviors essential for peace. This encompassed various aspects such as administration, care, and education.

Simultaneously, the lords emerged within the warrior hierarchy, tasked with safeguarding the well-being of the people and their property from external threats. Each manor within the English landscape boasted its own church, further highlighting the integral role of religious institutions within the local community. Together, the combined efforts of the clergy and the warrior class contributed to the development of a cohesive and protected society, where both spiritual and physical needs were attended to.

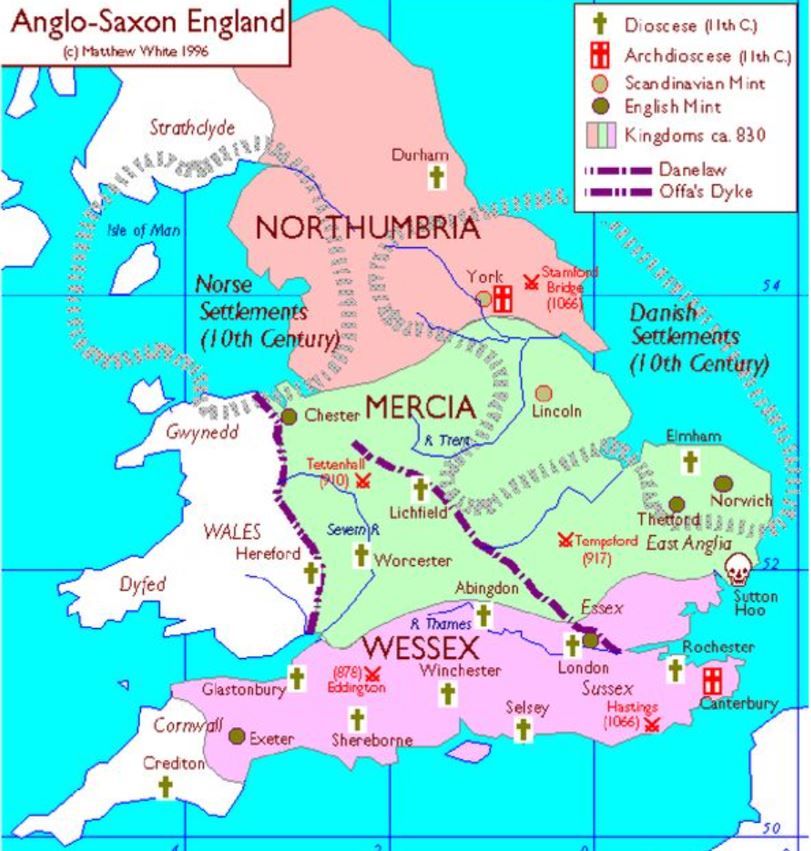

The Vikings and Danes from 800–1060 AD

During the Danish invasions of England around 850 AD, the main thrust of their forces moved from the northeast towards the south, leaving Cheshire on the periphery of these conflicts. In this precarious position, Cheshire took on a crucial role as an English bridgehead, serving as a defensive stronghold against both the Welsh to the west and the Danes to the north and east. The Welsh, with their strategic position in the hills, and the persistent Viking threat from the north posed ongoing challenges to the security of England as a whole. Cheshire, positioned between these two potential sources of danger, played a vital role in holding them at bay and safeguarding the English territories from their encroachments.

Figure 5: Norse and Danish Settlements before the Norman invasion - 1000 AD

Paternal DNA of my Ancestors is Q-L804

We know from history and artifacts of the Wirral peninsula, south of Liverpool, England, that there is documented evidence of Norwegian Viking settlers. Ancient Irish Chronicles report the first peaceful settlements by the Norwegian Vikings in 902AD in the Wirral Peninsula, however 30 years later they came inland with repeated raids on Chester, England after the peninsula became full of Norse settlers seeking additional land to settle.

My paternal Y-DNA is a subclade of Q-L804 that likely came from Norway during the Norwegian settlements in the Liverpool area between 902AD and 1050AD before the Norman invasion in 1066AD. Watch this video "migration path of Q DNA haplogroup" if you are interested in the Y-DNA of my ancestors and where they came from.

By the year 1066 AD, the rural economy of Cheshire brimmed with potential. The breeding of domesticated animals and the cultivation of grains yielded surpluses that provided resources to support other profitable crafts. Industries such as pottery, metalworking, spinning, weaving, milling, baking, and brewing thrived. This flourishing economic landscape gave rise to specialization and interdependency among different trades and crafts. Our ancestors were engaged in bustling activity and achieved notable economic success.

Amidst this development, a distinct rural economy took shape in Cheshire. The region held strategic importance for defense purposes and served as a trading hub for salt. Cheshire's countryside lay on the outskirts of Mercia and remained sparsely populated, offering ample room for growth and expansion.

The Normans – 1066 – 1348 AD

The arrival of the Norman invaders brought about a ruthless seizure of power, disrupting the well-established economic system in which our ancestors lived. Unlike previous assimilations of foreign invasions in Cheshire, the local inhabitants, known as Earl Edwin's 'Chester-men,' fiercely fought back. The confrontations with the Welsh and the Danes had instilled a sense of English pride and resistance. However, this time, William the Conqueror prevailed with great brutality, constructing his castle at Chester. The aftermath was devastating, with vast stretches of land destroyed, villages demolished, crops burned, livestock slaughtered, and the people left landless, homeless, and dispossessed. In 1069 AD, a final attempt at local resistance was brutally crushed, and draconian measures were imposed to discourage any future uprisings. The severity and ruthlessness of the Norman imposition laid waste to much of the land.

In the wake of the Norman conquest, our ancestors in Cheshire found themselves transformed into serfs and laborers, bound economically, socially, and legally to the land through the property rights of the lords. The lords owned the land, which in turn owned the feudal tenant, while the tenants owned the cattle. The value of a lord's estate was determined by the number of tenants and their cattle. However, the true value of the cattle lay in the knowledge and expertise of breeding, husbandry, and the various practices associated with producing milk, butter, cheese, meat, and leather. This knowledge was deeply rooted in the customs and practices of the tenants. The feudal lords, motivated by maintaining tax revenues and accumulating wealth in larger estates, were not engaged in trade. This clashed with the mercantilist world where innovation, productivity, and surplus generation were sought through technological advancements and trading of agricultural produce and livestock. Unfortunately, the English lost the war with the Normans, and as a result, our ancestors were taxed into poverty. This created a sense of despair and a lack of incentive to work and improve their circumstances. The tragic consequence was a stagnating existence with diminishing returns from heavy taxation. A complex battle unfolded as feudal lords attempted to tax any signs of success, only to witness the stifling of enterprise and subsequent decline in revenues due to the lack of motivation for increased productivity. This 'tax paradox' ultimately led to the downfall of the feudal system. It was during the Norman rule that the original nave of St. Bartholomew's in Wilmslow was built in 1264 by Sir Richard Fitton who was the Manor of Bollin.

Pownall Fee beginnings

Pownall Fee traces its roots back to the remarkable period of England's great migration wave following the historic Norman Conquest of 1066. The esteemed Pownell family, recognized for their invaluable aid during the pivotal Battle of Hastings, were generously rewarded by Duke William of Normandy with extensive lands. It is from this noble family that the village derives its distinguished name. The term "Fee" refers to a knight's fee, denoting land granted as a form of feudal service.

The concept of a knight's fee was introduced to England by the Normans hailing from Northwest France, who brought it along during their invasion and subsequent settlement in 1066 AD. Norman rulers would allocate or "lease" land to the brave Norman warriors who played a crucial role in their conquest campaigns. This system served as a means of rewarding their loyal supporters while establishing a hierarchical and feudal structure in the newly acquired lands.

The Norman Conquest stands as a pivotal event characterized by the invasion and subsequent occupation of England by a formidable army composed of thousands of Normans and Frenchmen, all under the leadership of the Duke of Normandy in the year 1066 AD. The origins of the Normans can be traced back to their Viking ancestors hailing from Scandinavia.

In 911 AD, the French ruler Charles the Simple made a momentous decision to grant land in Normandy, France to a group of Vikings as part of a peace treaty. This strategic move aimed to secure protection against the incursions of other Viking raiders who had previously ravaged inland France through the Seine River. The Norman settlement flourished, with the Vikings swiftly assimilating into the local culture. They embraced Christianity, adopted the French language, and intermarried with the native French population.

After a span of 250 years, the ambitious Normans turned their gaze across the English Channel, harboring aspirations of conquering England. Their successful assimilation and consolidation of power in Normandy provided them with the foundation and confidence to embark on this audacious undertaking.

Figure 1.2 – Map of the Norman invasion of England.

The Black Plague – 1348 AD

Cheshire endured challenging times, further exacerbated by the devastating impact of the Black Death in 1348 AD, which claimed the lives of 40% of the population within a span of two years. Amidst this tragedy, the resilient and fiercely independent Anglo-Saxon culture, which had been suppressed under Norman rule, began to resurface in significant ways. The population decline resulting from the plague created a labor shortage in farming communities, leading to the gradual erosion of the feudal systems established by the Normans.

Over the course of nearly two centuries, the distinct English culture gradually reemerged, breaking free from the oppressive grip of the Norman feudal system. New rights and obligations were established through important documents like Magna Carta, which gained parliamentary scrutiny and flourished as a widely accepted code of conduct, embedded within English Common Law. The English language, spreading its influence, became instrumental in sealing deals and facilitating trade, connecting people across larger networks and more distant exchanges.

Cheshire – 1500 - 1600 AD

Prior to the onset of the Industrial Revolution, Cheshire thrived as a prosperous region, characterized by a motivated and forward-looking population, poised to embrace the emerging economic transformations. The necessary conditions were already in place, including a reduction in established authority, a growing sense of diversity and choice, the emergence of cooperative institutions, the adoption of the scientific method, and a direct recognition of successful innovators.

Britain experienced its civil war early on, resulting in the execution of the King, and our Cheshire ancestors played a significant role in this movement. Cheshire became a haven for dissenters who rejected the imposition of beliefs by newly empowered individuals. Having endured the hardships of the plague and famines, the population of England nearly doubled between 1541 and 1651, surpassing 5 million people from an initial count of 3 million, reflecting a remarkable growth and resilience in the face of adversity.

St. Bartholomew's Church in Wilmslow remodeling began in 1490 and major rebuilding work was directed and paid for by the rector Henry Traffer and completed around 1522. Lawrence Pierson (b1620) great-grandfather may have a mason that helped complete this work.

Freeholders

In the year 1612 AD, a significant event unfolded. Sitting tenants who diligently paid their rent were presented with a remarkable opportunity to become "fee farmers" by acquiring the "freehold" of their farms through a sale. This shift in ownership granted them the ability to possess and transfer their land freely. This practice, deeply rooted in Anglo-Saxon tradition, resulted in legally binding agreements that proved to be highly advantageous. Lawrence Pearson (b1620) was likely a freeholder as his will included land that was divided between his four children.

These opportunities, though not as common in larger farms in the south or in other European countries, were available to numerous small farmers in Cheshire. The economic implications of these developments were profound. The emergence of a diverse group of small working farmers who owned their own land fostered a keen interest in competitive technological innovation and a strong focus on maximizing returns on their investments. The power of property ownership shattered the grip of monarchs and the church, allowing for the exploration and evaluation of alternative belief systems.

Quakerism – 1648 AD

Quakerism had its beginnings in the north of England around 1650, it was based on the personal introspection of a shoemaker's apprentice, George Fox. The Society of Friends had their own strictly independent relentless beliefs:

- Gods’ way was through internal mediation deep down in every individual

- God was present in every single individual human soul, as an inner light, an emotional, not conscious, moral urgency & empathy which mediated & guided all decisions

- Anyone and everyone were free to help and preach in his own way. This was a very basic re-emphasis of the individual freedom long part of the Anglo-Saxon culture. Such beliefs were inaccessible to manipulation by others.

The Quakers had no tolerance for haughty preachers who claimed exclusive access to God and held elitist beliefs. They rejected the imposition of formal creeds, oppressive codes of conduct, extravagant displays of wealth, and the use of threats of damnation or imprisonment. The Quakers firmly stood against the enforcement of beliefs that sought to control them.

One particular issue they resisted was the payment of tithes, which they viewed as unjust impositions that perpetuated immoral authoritarian biases and contributed to the persecution of dissenting minority groups. As a result of their refusal to swear oaths or pay tithes, the Quakers faced legal persecution. They often encountered discrimination in pursuing conventional careers. However, many Quakers thrived in alternative business ventures and some even chose to immigrate to the New World. It was during this era that Lawrence Pearson (b1620) and his family made their living in Chester County.

The tenets of Quaker religion were the following:

1. Refusal to pay tithes, which they esteemed a Jewish ceremony revoked by the coming of Christ.

2. Refusal to pay for buildings or maintenance used for worship as these buildings were filled with superstition and idols.

3. Obedience to “Swear not at all” which they would not do in any case to human law or courts.

4. The custom of uncovering their heads or pulling off hoods to pay homage to men passing by was seen as unnecessary homage to men.

5. Their resolution of assembling for the worship of God in their own homes outside of the Church of England.

6. The necessity of publishing and preaching the truth by reproving vices and immorality openly in the streets and markets.

7. Refusal to make use of the established Priest or Ministers either in marrying, burying, or paying fees for such.

8. Testifying against wars and fighting and that it is inconstant with the precepts of Christ “love you enemies. Do good to them that hate you”.

Sufferings of the Quakers

The primary reasons for the persecution of the Quakers, which resulted in their suffering, were their refusal to pay tithes, their practice of gathering for worship in their homes instead of attending the established church, and their objection to swearing oaths. In addition to the oaths required in legal proceedings of that time, oaths in England also included allegiance oaths to the King, which involved pledging loyalty to the King and rejecting any directives from the Pope that contradicted the interests of the King of England.

I “name of person” do truly and sincerely acknowledge, profess, testify and declare before God and the World, that our Sovereign Lord King James is lawful and rightful King of this realm, and of all other his Majesty’s dominions and countries, and that the Pope, neither of himself, nor by and authority of the church or see of Rome, or by any other means with any other, hath any power or authority to dispose the King, or to dispose of any of his Majesty Kingdoms or Dominions, or to authorize and foreign Princes to invade or to annoy him or his countries, or to discharge any of his subjects from their allegiance and obedience to his majesty, or to give license or leave to any of them to bear arms, raise tumults, or to offer any violence or hurt to his majesty royal person or government, or to any of his subjects within his majesty’s dominions. Also I do swear from my heart, that notwithstanding and declaration, or sentence of excommunication, or deprivation, made or granted, or to be made or granted by the Pope, or his successor, or by any authority derived, or pretend to be derived, from him or his see, against the said King, his heirs or successors, or any absolution of the said subjects from their obedience, I will bear faith and true allegiance to his majesty, …. And I do believe, and in my conscience am resolved, that neither the Pope, nor any other person whatsoever, hath power to absolve me of this Oath, or any part thereof, which I acknowledge by good and full Authority to be lawfully administered to me….

The Quakers in Cheshire County often experienced distressing incidents during their home meetings. Constables would frequently forcibly enter their homes, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of all individuals present for extended periods, sometimes spanning months or even years, without a fair trial. In addition to the unjust imprisonment, the constables and priests would seize their property and livestock as compensation for unpaid tithes, resulting in some Quakers becoming homeless and impoverished. The Quakers also endured substantial fines imposed for hosting Friends' meetings in their homes, further contributing to their suffering and hardships.

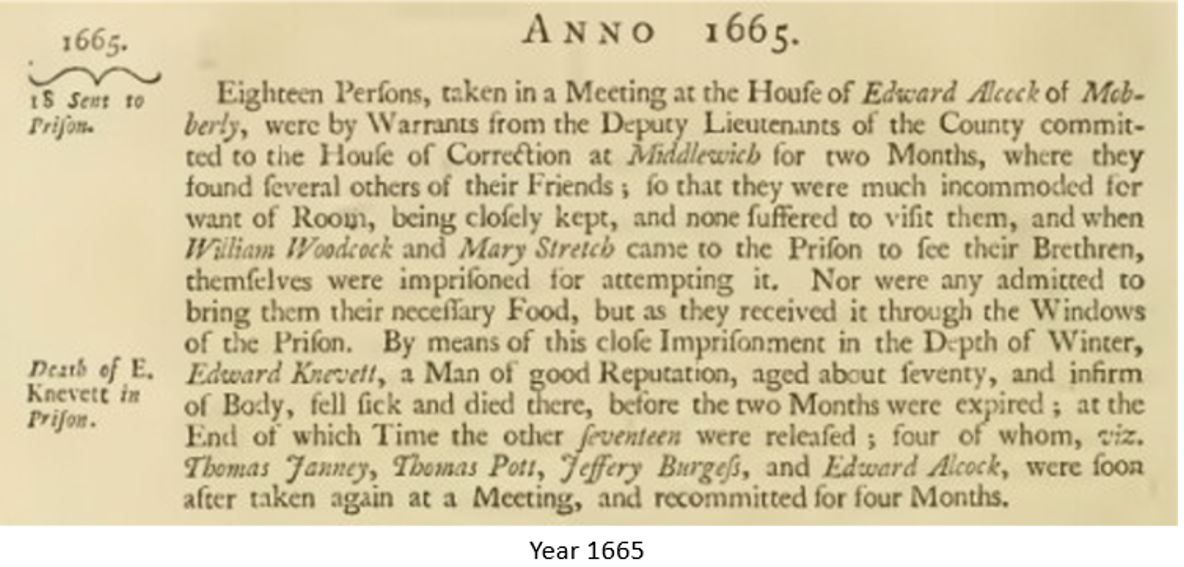

Fig 1.7 – Taken from the book “A collection of the Sufferings of the people called Quakers” Volume 1 Chapter 7 Cheshire, by Joseph Besse, London, 1753 AD. (Note: substitute s for f in the text above)

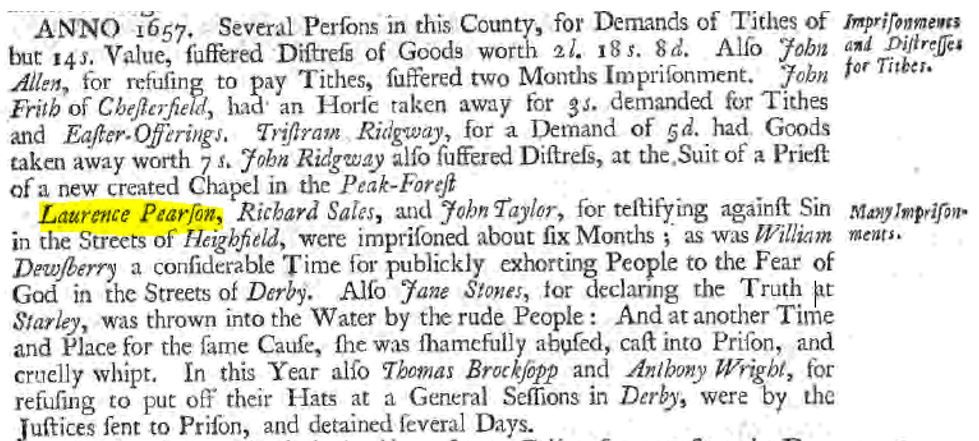

The aforementioned article provides a detailed account of Thomas Janney's imprisonment in 1665, who happens to be Lawrence's father-in-law and my 10th great-grandfather. Both Lawrence Pearson and his brother also faced imprisonment. In 1657, Lawrence Pearson of Wilmslow Parish bravely refused to pay a tithe and had a valuable horse, worth three pounds, seized as payment for an eight-shilling tithe—a sum significantly exceeding the actual tithe owed. Subsequently, in 1665, Lawrence Pearson of Pownall Fee was apprehended during a Quaker meeting and incarcerated for a period of two months. Furthermore, in 1657, Lawrence Pearson endured imprisonment for testifying in the streets at Highfield, County Derby. Lastly, in 1660, Robert Pearson, Lawrence's brother, was imprisoned for his refusal to take an oath.

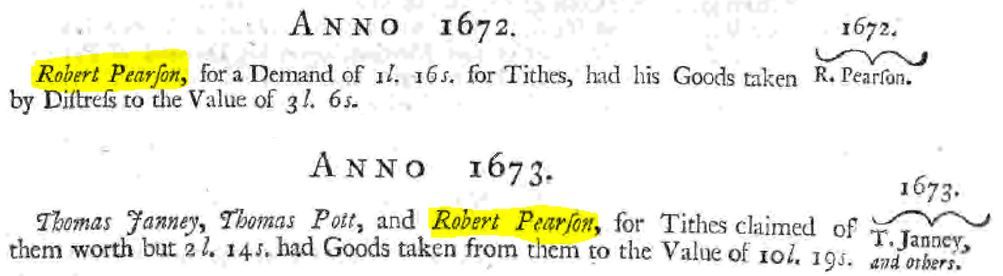

Fig- 1 – Robert Pearson (Lawrence’s brother) goods taken from him.

Lawrence’s brother on two occasions had property taken from him in 1672 and 1673 for Tithes not paid. The value of the goods taken were 4 to 5 times more than the tithes owed which was a common practice of the Church and State. Lawrence Pearson also was imprisoned for 6 months in 1657 for testifying in the streets in Derbyshire. Derbyshire is 38 miles southeast of Wilmslow.

Fig 1.8 - From Beese’s “Sufferings of the People called Quakers” Laurence Pearson imprisoned 6 months in Derbyshire, England, page Volume 1 page 137.

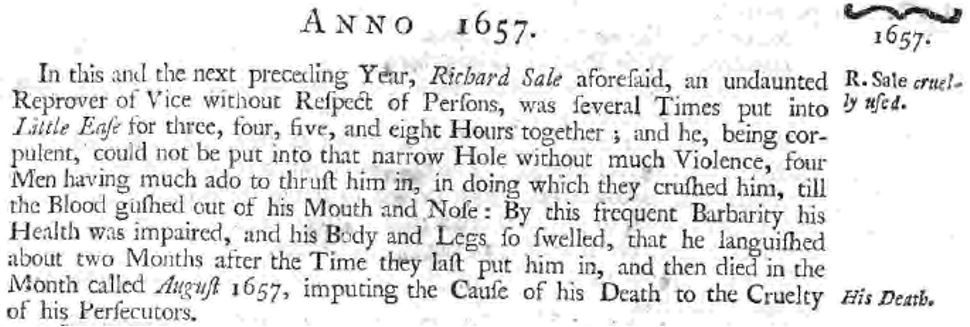

The sufferings endured by Quakers persisted from the inception of Quakerism in 1650 until the enactment of the "Act of Toleration" by King William III in 1689. The local city jails and larger prisons were known for their abhorrent conditions, with cruel jailers subjecting prisoners to beatings and confining dissenters for months in dreadful dungeons. In Cheshire jail, a particularly torturous site known as Little Ease was employed. It consisted of a hole carved into a rock, measuring 17 inches from side to side and 4 ½ feet from top to bottom. It was within this cramped space that Quakers were subjected to torture and mistreatment.

Fig 1.8 – Cheshire Quaker in 1657 died after beating and 2 months in the “Little Ease” (Note: substitute s for f in the text above).

Chapter 2

Robert Piers (Pierson) (b1577)

Ann Shawcrosse (d1655)

Generation 1

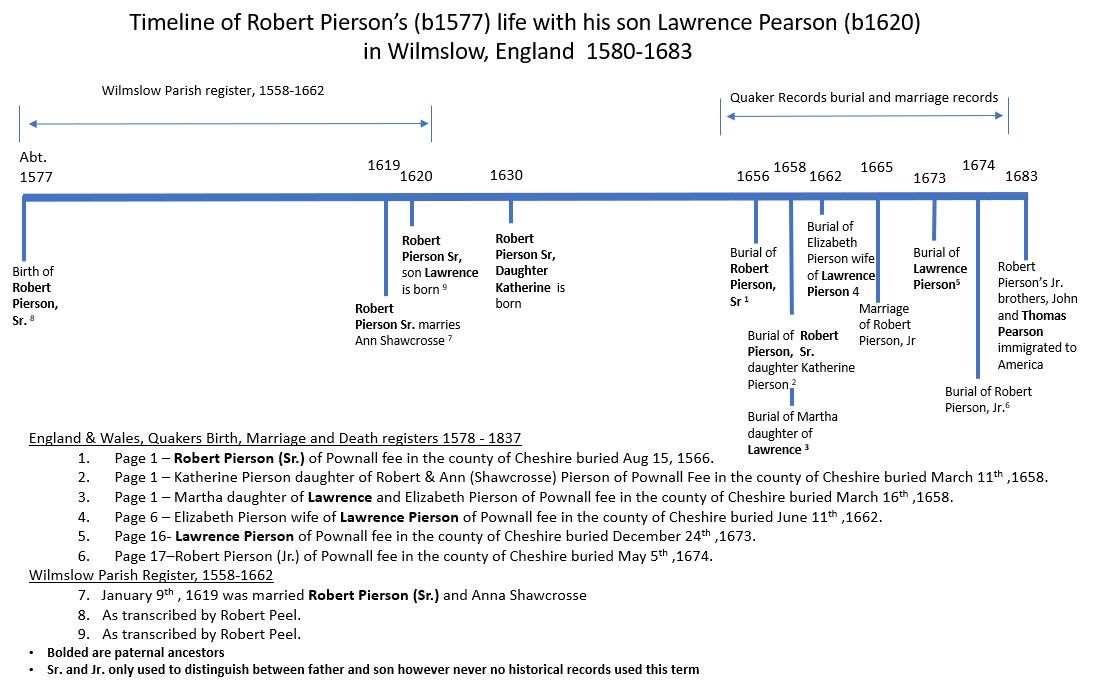

Originally, Edward Peersonne was believed to be Lawrence Pierson's (b1620) father, as stated first in Corinne Hanna Diller's genealogy book "Quaker Pearsons" published in 1981. However, a more plausible alternative is Robert Piers (b1577), who is listed as Robert Pierson in the same Quaker burial records as Lawrence Pearson and his wife Elizabeth. Records show that Robert Piers (Pierson) was born to John Piers in Wilmslow Parish in Cheshire however records are sketchy on birth dates and spelling of names.

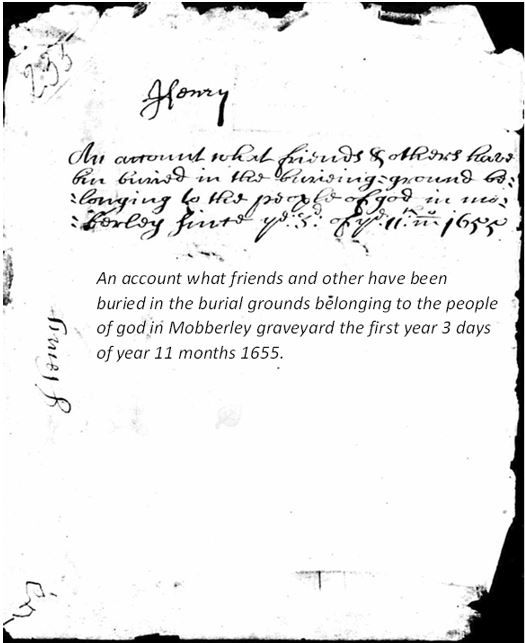

First Quaker Records in Wilmslow, England

Recognizing the need to maintain accurate records of births, deaths, and marriages, Quakers took it upon themselves to document these events. They understood the importance of having records in case their property rights were challenged in local courts or by the Church of England. Since Quakers did not perform their marriages in the Church of England, they required a reliable record of these significant life events and witnesses, similar to how their local St. Bartholomew's Church had previously maintained such records.

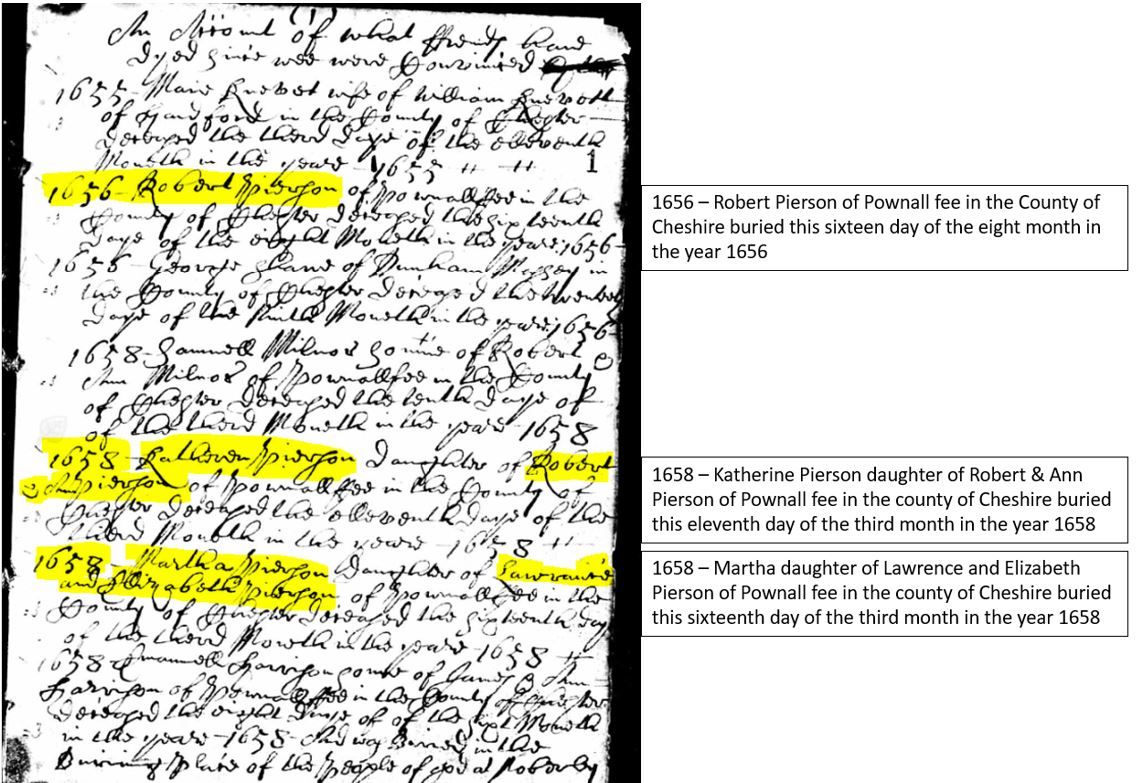

The earliest available records from the Quaker Cheshire area pertain to the deaths that occurred among the "Friends." The following is an introduction page from the Quaker Burial records of the Quakers. Mobberley graveyard is the graveyard next to St. Bartholomew Church in Wilmslow, England

Fig 2.1 – First page of Quaker burial records from 1655 – 1742

Listed below is the evidence and reasoning why Robert Pierson (senior) is most likely the father of Lawrence Pierson. To make reading clearer, I will use senior for the older Robert Pierson and junior for the younger who is his son with the same name although the word senior or junior was not used in the records.

1. We know there were at least two Robert Pierson that lived around 1650 near Wilmslow since they are listed in the Mobberley Quaker burial records at different dates, 18 years apart in 1656 and 1673.

2. Robert Pierson (senior) was likely the father of Lawrence Pierson, Katherine Pierson, and Robert Pierson (junior).

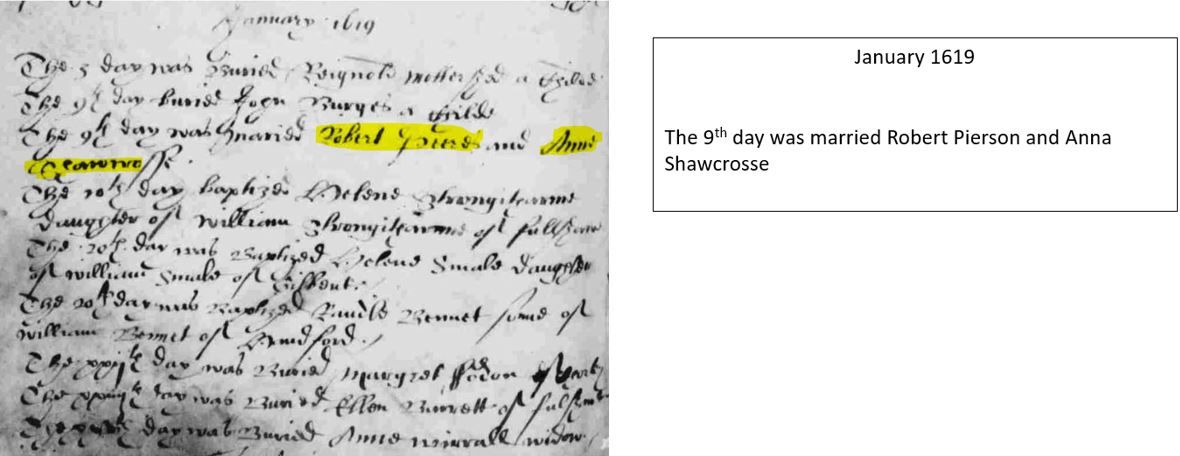

3. Robert Pierson (senior) wife was Ann Shawcrosse. Records show they married in 1619 in Wilmslow at St. Bartholomew’s church.

4. The Quaker burial records lists Robert Pierson (senior) buried in 1656 and recorded his daughter Katherine Pierson buried two years later in 1658, listing Robert Pierson (senior) and Ann as parents.

5. Robert Pierson (junior) was 26 when his father died and was married in 1665 at the age of 33 With no records of an earlier marriage, indicating Katherine Pierson is likely not his daughter.

6. Robert Pierson (junior) burial is listed in 1674, 18 years after Robert Pierson (senior).

7. Lawrence Pierson has his burial listed in 1673 in the Quaker’s records

8. Lawrence Pierson will mention his brother Robert Pierson (junior) as an executor.

9. Robert Pierson’s (senior) three children’s burials are recorded in the Quaker’s records. Robert Pierson (junior) at age 44 in 1673, Katherine at age 31 in 1657 and Lawrence at age 53 in 1674. He may have had more children however records could not be found for them.

10. Nowhere in the Quaker burials does it mention Edward Peersonne. It is likely that Edward was not a Quaker whereas all of Lawrence’s family are listed either in burials or marriages in Quaker records.

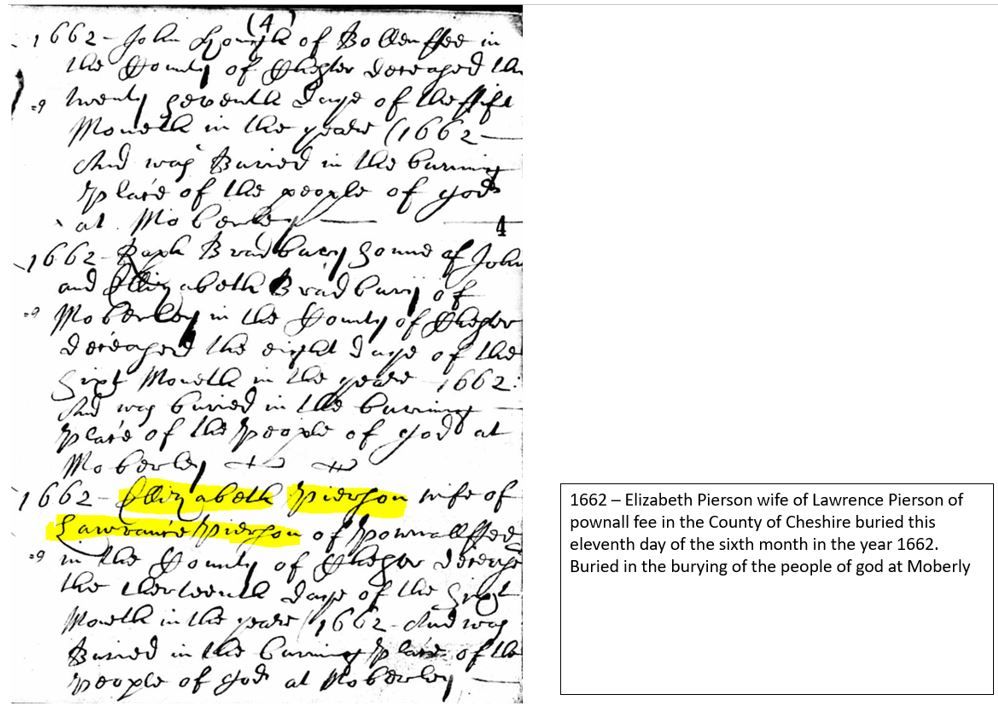

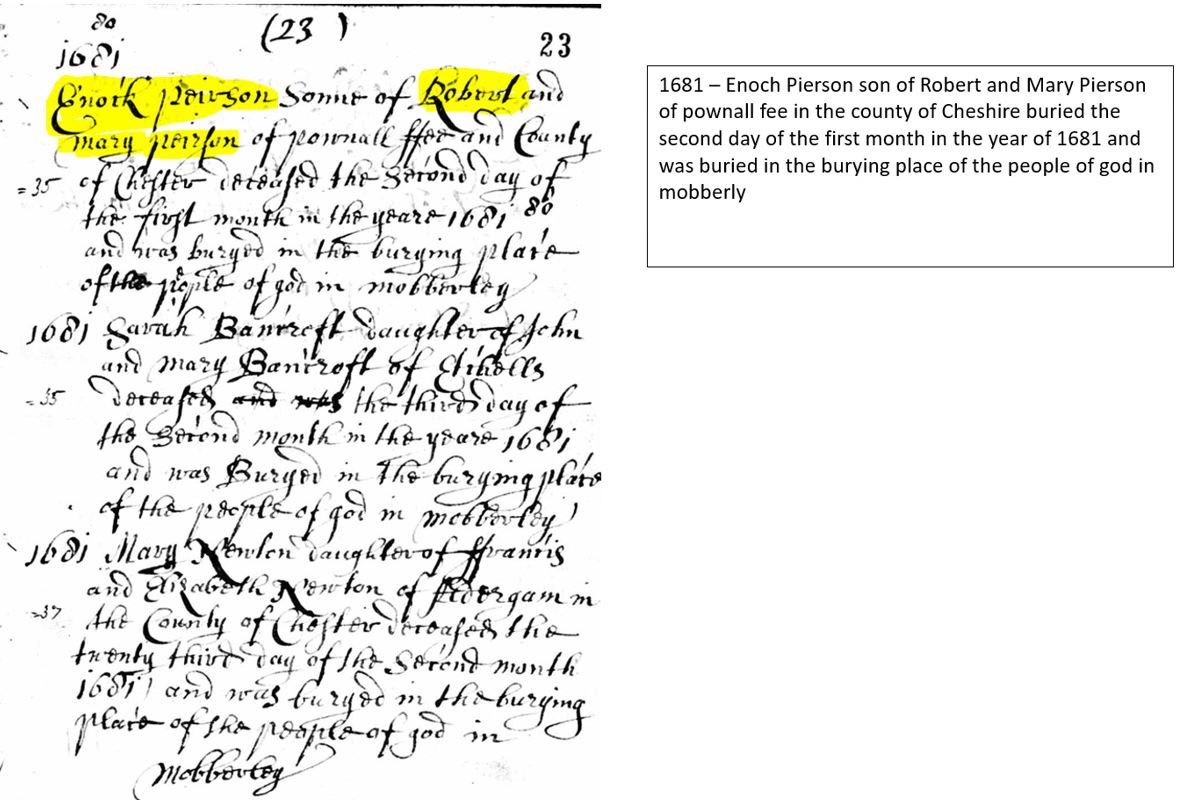

Fig 2.2 – Page 1 - Quakers burial records listing Pierson’s burials, Lawrence’s father, sister, and daughter.

Fig 2.3 – Page 6 - Quakers burial records listing Lawrence Pierson’s wife Elizabeth burial

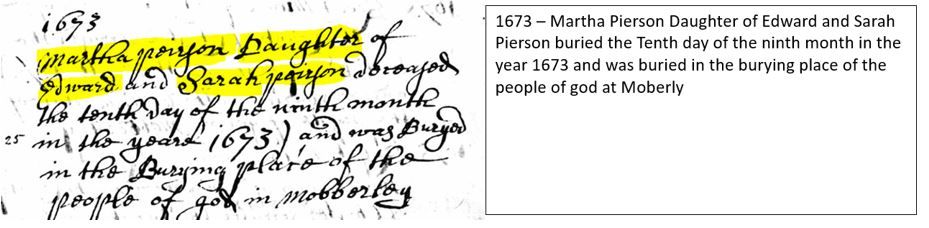

Fig 2.4 – Page 15 - Quakers burial records of Martha Pierson, Lawrence Pierson’s granddaughter.

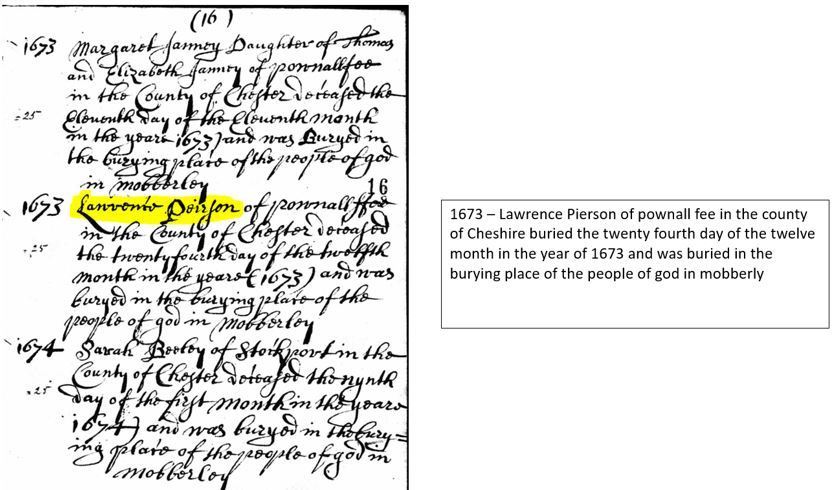

Fig 2.5 – Page 16 - Quakers burial records, Lawrence Pierson burial in 1673

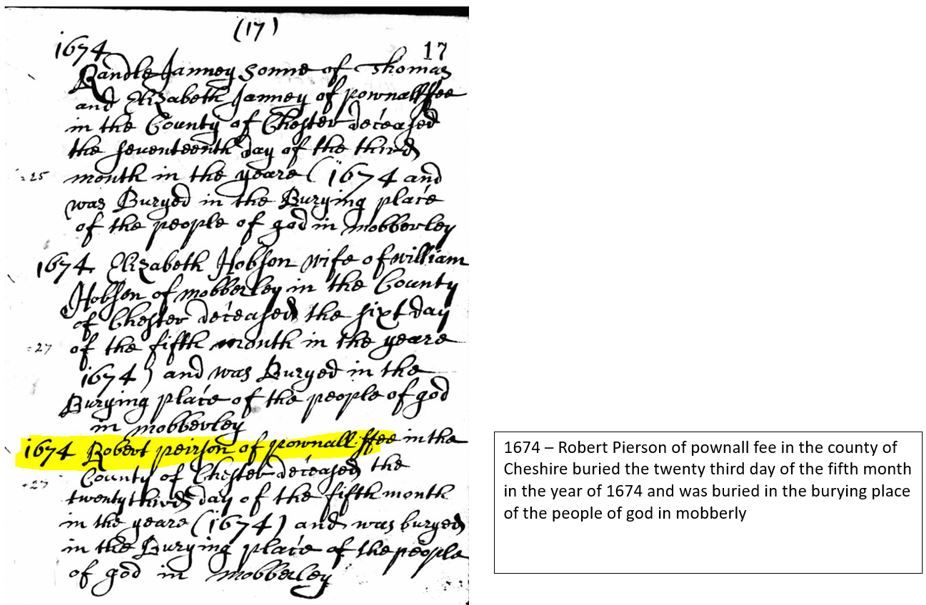

Fig 2.6 – Page 17 - Quakers burial records listing Robert Pierson (junior) burial in 1674, Lawrence Pierson’s brother

Fig 2.7 – Page 23 - Quakers burial records – Enoch’s burial who is the son of Robert Pierson (junior)

The Quaker records make Robert Pierson the probable father for Lawrence Pierson. In addition, below is a record of Robert Pierson marriage in January 1619 to Anna Shawcrosse. A year later in May 1620 Lawrence was born.

Fig 2.8 – Marriage record at St. Bartholomew’s Church in Wilmslow Parish of Robert and Ann Shawcrosse

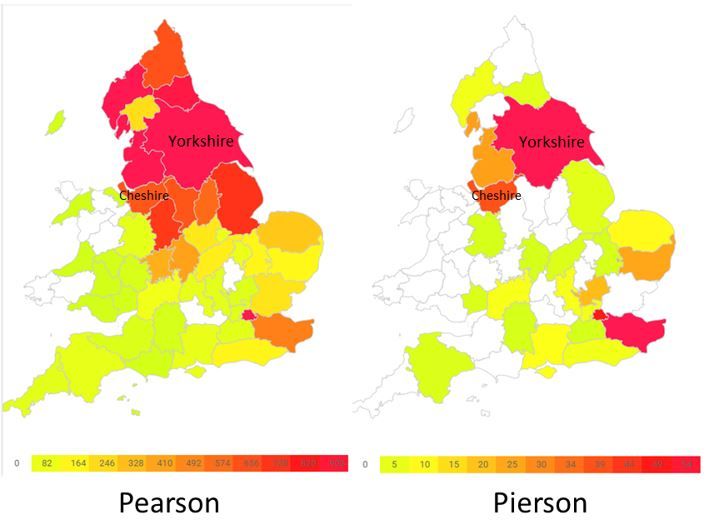

The Pearson/Pierson name in England was present primarily in the north of England in the 1840 census. Lawrence was a mason and likely his father was too. Masons needed to travel for their work when their last job at the castle, church or cathedrals were finished to stay employed. It is possible that Robert came from York, England. Robert Pierson’s name appears in the records in York, England with a baptism on May 22, 1580, and his father’s name was John Piers

Fig 2.9 – Pearson and Pierson surname distribution concentrations by English counties

Chapter 3

Lawrence Pierson (b1620)

Elizabeth Janney (b1620)

Generation 2

Lawrence Pierson was born in 1620 or 1621 to Robert Pierson during unsettling times in England. He was a young adult during the English Civil War that devastated England between 1642–1651. It was during this period many battles occurred between the English Parliament army and the Royal army of King Charles I. By the end of the 1630s, relations between the English factions became increasingly tense with arguments over religion, society, morals, and political power becoming increasingly evident in the years before war broke out. There were deep divisions over what religious practices, forms of worship and the organizational structure the Church of England should have. King Charles the first believed he was king by the divine will of God and therefore his decisions could not be challenged or even questioned. He was deeply religious and preferred a High Anglican form of worship that included hierarchy, ceremonies, rituals, and lavish ornamentation much like the Roman Catholic religion that English protestants distrusted. He believed the hierarchy of bishops and priests are to be important and it appeared to the Puritans he was leaning toward Catholicism after marrying his wife Henrietta who was raised Roman Catholic in France. The Puritans, who were extreme Protestants, wanted a purer form of worship without rituals and religious icons and images and believed they had a personal relationship with God and did not need bishops or priests.

English Civil war

The war between the King and Parliament was also about money needed for external wars and the taxation which Parliament needed to approve.

There are no records that Robert or his son Lawrence Pierson fought in the English Civil War on any side. However, Lawrence spent all his young adult life in these times, and it is likely he picked a side. With his Quaker conversion in the 1650s and his imprisonment for preaching in the street and not paying tithes to the Church of England he likely sided against the King and his Church.

Even after the English Civil War and the execution of King Charles I, there was still uneasiness and strong disagreements in the country with a divided parliament. Oliver Cromwell governed the Commonwealth of England as “lord protectorate” after King Charles I beheading. Soon after Cromwell’s death in 1658, the country returned to being a monarchy after Parliament crowned King Charles I son who was in exiled in France until he was crowned King of England. In turn, religious dissenters to the Church of England were persecuted and jailed.

Quakerism spread across Britain during the 1650s and 1660s and there were around 50,000 Quakers. The Quaker religion was radical and a threat to the King and the Church of England since they didn’t believe in tithes, priests, and swearing to oaths. This is in the same time Robert, Lawrence and their family converted to Quakerism.

Quakers Friends

In 1647 George Fox started a movement across England that made its way to Cheshire. Early Friends did not believe that a priest or magistrate, or even a Quaker meeting, could perform a marriage. Only God could do that. Marriages took place in a silent meeting where the man and woman rose and affirmed their commitment to each other before God. Those present signed a certificate witnessing that the marriage had taken place. Careful records of witnesses were kept in hope that courts would recognize the marriage and the legitimacy of the children in it, thus avoiding challenges to inheritance.

The testimonies of Friends and a sense of God’s presence permeated Quaker families. Families attempted to live their lives in daily obedience of God. Simplicity, honesty, and order were valued. Card-playing, dancing, and liquor were forbidden, and anger often repressed. Emphasis on humility and pacifism helped prevent domination and use of violence. Participation in meetings for business taught husbands and wives to listen and achieve agreements in a friendly manner that addressed the needs of both spouses.

Will of Lawrence Pierson

The records for our ancestors start in Wilmslow, Cheshire, England where in the small ancient village of Pownall Fee, Lawrence Pierson (b1620) lived and worked as a masonry and a farmer and he owned some land as a freeholder. His will stated he owned plowshares that he passed on to his oldest son Edward

“I give unto my son John £4, unto my son Edward the dish board, little plow and the little pair of plow irons, etc.”

Four pounds in today’s money is about $1000.

“It is my will that the rest of my goods etc. be divided into four equal parts and three parts thereof to be divided into equal portions unto my son John, unto my son Thomas, unto my daughter Sarah….and the fourth part to my daughter Mary”.

Lawrence’s assets included “A bargain of ground from Peter Higginbottom mentioned in a specialty” valued at £4, 11shillings ($1,200 in 2022). The area of land was not recorded.

Mary Pierson’s portion of the will was set apart from the other children. She was 25 years old when Lawrence died. Her mother, Anne Worth, Lawrence’s first wife, died when she was born in 1647. Why was her inheritance separated from her stepbrothers and stepsister? Lawrence’s other daughter Sara was only 14 when he died however, they didn’t provide a special administrator for her inheritance. Why did Mary get special attention? Did she have special needs? Mary is not listed in the Quaker records as ever married.

According to the passenger list of the Endeavor ship, Mary Smith traveled to Pennsylvania with Thomas Pearson and Margery Smith Pearson. While the passenger records initially identify her as Thomas' sister, it is more likely that she was actually Margery's sister, sharing the same maiden name. In the Quaker records, a Mary Pierson is mentioned until her death in 1698. However, she was the widow of Robert Pierson's (junior), who did not immigrate to America. Therefore, she cannot be Lawrence's daughter.

It is probable that Mary Pierson arrived in America with her brother Edward in 1687, four years after Thomas. Unfortunately, there are no records indicating that she ever married.

Lawrence’s Will, Parish records and Quaker records recorded Thomas Pearson (b1653) as his son and our ancestor who immigrated to America in 1683.

Lawrence and Elizabeth Pierson had five children and Lawrence had another child, Mary, from an earlier marriage.

In the Probate Registry, Chester, England

1673, February 21,

I, Lawrence Pierson of Pownall Fee, Co., Chester, a Mason.

I give unto my son John £4, unto my son Edward the dishboard, little plow and the little pair of plow Irons, etc. Unto my daughter Mary 1/3. It is my will that the rest of my goods etc. be divided into four equal parts and three parts thereof to be divided into equal portions unto my son John, unto my son Thomas, and unto my daughter Sarah. And the fourth equal part being divided, as aforesaid, I give unto my executor to administer to my daughter Mary for her issues necessities according as they in their wisdom and discretion shall see occasion.

Executors my brother Robert Pierson of Pownall Fee, Mason and John Johnson of Baguly, yeoman, and Randle Janney of Pownall Fee, husbandman.

Signed: Lawrence Pierson.

Witnesses, Peter Burges, John Hobson, the mark of O for Richard Neild. Proved 20 June 1674 by Jo. Johnson one of the Executors, named. Power reserved to Robert Pierson, Randle Janney being dead.

Lawrence Pearson's will included a division of his property into four parts. He directly bequeathed three shares to his sons: John (age 19), Thomas (age 20), and his daughter Sarah (age 14). However, the fourth share was to be managed by the executors, including his brother Robert Pierson (who passed away one year later), John Johnson, and Randle Janney (his brother-in-law, who also passed away one year later). This fourth share was intended for the welfare of Mary (age 25).

Mary was the only daughter of Lawrence and his first wife, Anne Worth, who sadly passed away in the same year Mary was born. It is possible that Anne died due to complications from childbirth. Mary Pierson's baptism is recorded at the Wilmslow Church on October 31, 1647, with her father Lawrence mentioned, but her mother's name is not listed.

During the 1600s, England experienced devastating outbreaks of smallpox, a highly contagious and deadly disease. Smallpox has long been recognized as a lethal illness that afflicted countless individuals. Unfortunately, many of our ancestors fell victim to this disease, resulting in premature deaths. It is estimated that, on average, three out of ten individuals succumbed to smallpox during these outbreaks, highlighting the widespread impact and severity of the disease.

Fig 3.2- Today’s map of Wilmslow and Styal near the Manchester airport

Chapter 4

Thomas Pearson (b1653)

Margery Smith (b1658)

Generation 3

Thomas Pearson, the son of Lawrence Pearson from Wilmslow, England, belonged to the Quaker community. Like his father and many fellow Friends, Lawrence faced fines and imprisonment due to their refusal to tithe the church, take oaths, or preach openly in the streets. There are records indicating that Lawrence was either fined or incarcerated by the local magistrate on two separate occasions due to his beliefs.

Thomas lost his father in 1673 when he was just 19 years old, and his uncle Robert passed away a year later in 1674. Despite the ongoing persecution faced by Quakers in Cheshire, Thomas chose to wait until he was 29 years old before embarking on his journey to America. The reasons for this delay and the factors that influenced his decision to immigrate in 1683 deserve exploration. To understand these circumstances, we must delve into the motivations and opportunities that presented themselves to Thomas, as well as the individuals who played a role in making his migration possible.

William Penn – The founder of Pennsylvania

William Penn was born in London in 1644, the son of Admiral Sir William Penn. Despite his high social position and an excellent education, he shocked his upper-class associates by his conversions to the beliefs of the Society of Friends. In 1668 William Penn converted to Quakerism while in Ireland. Later that year he was arrested for attending a Friends meeting at Cork. After his release, he returned to London, England and confronted his father about his new-found religion.

Penn discusses Quakerism ideals with his father. His father didn’t like him going against the Church of England and wanted to disown him, however never had the heart to followed through. In London he also meets with George Fox the founder of the Friends and in 1669 he writes the pamphlet “The Sandy Foundation Shaken” which attacked the doctrine of the trinity and was jailed without a trial. While in jail for 8 months he writes additional pamphlets on Quaker’s beliefs and is finally released. England passes the Conventicle Act in 1670 which provided severe persecution of Quakers and Baptists. This act was intended to suppress religious meetings conducted "in any other manner than what was practiced in the Church of England”.

Over the next year Penn is jailed again preaching outside a padlocked Quaker meetinghouse in London. Penn’s father dies at the end of 1670 and William inherits his father’s assets. Penn is in and out of jail over the next 10 years for various pamphlets he had written. In the meantime, he hears stories of George Fox voyage to America and small colonies of Quaker settlements in New Jersey from land bought from the Native Americans.

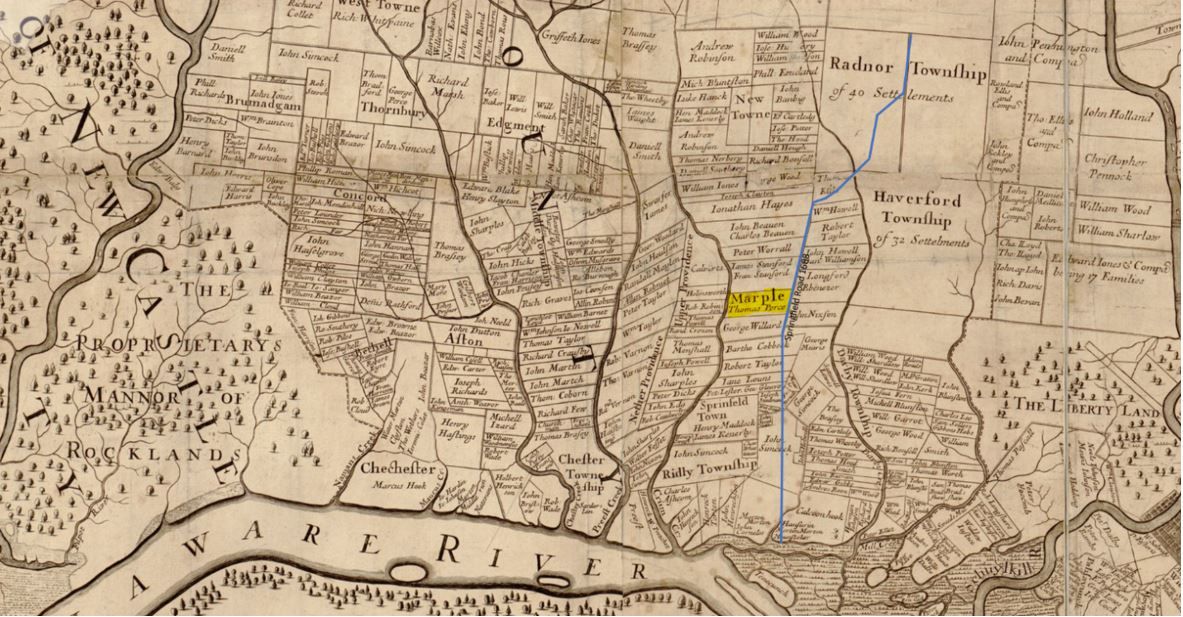

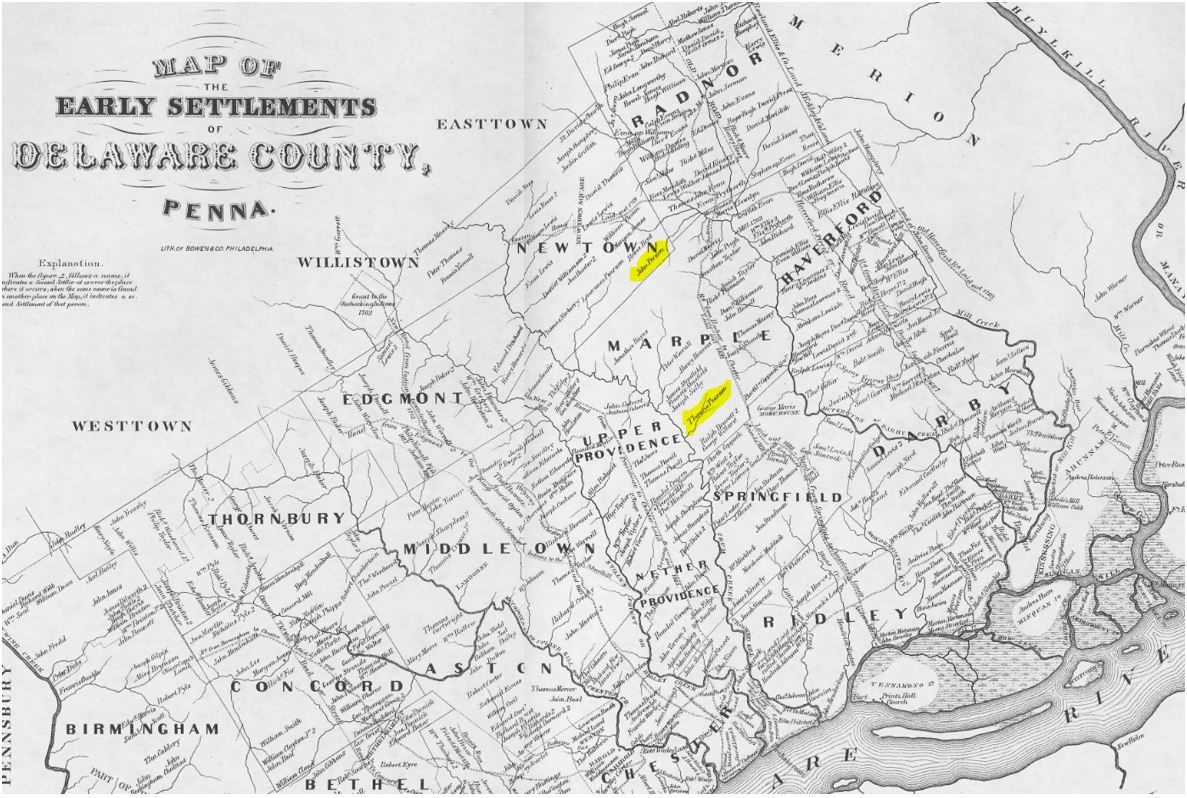

In 1680 William Penn writes to King Charles II asking him for land in America in exchange for the 16,000 pounds ($2.3 million in 2022) debt the King owes his father’s estate for money loaned to him during the war. In March 1681, the King agrees and signs over land in America to William Penn and the King calls it Pennsylvania. John Pearson secures land for him and his brother Thomas Pearson. They became one of William Penn's first purchases in England by receiving the grant of 259 acres of land to be laid out in the Pennsylvania Province, the deeds of lease for the tract being signed by Penn, March 2, and 3, 1681, in his land office, in historic old George Yard in Lombard Street. Later John formally deeded the tract to Thomas and purchase a farm 5 miles north over the line in Newton Township located on the map in Fig 4.7. A map below in Fig. 4.1 show the improved areas of Pennsylvania with the farm purchased by Thomas Perce (Pearson) in the township of Marple, even though his family did not arrive until Sept 1683.

Fig 4.1 -1681 map of improved part of the province of Pennsylvania in America – Thomas Pearson area in yellow highlight

In August 1682 William Penn sails to America on the ship Welcome a year before Thomas Pearson and his wife arrived in America. The sailing was plagued with smallpox. Out of 100 passengers 31 died, however Penn was immune because he survived smallpox as a child.

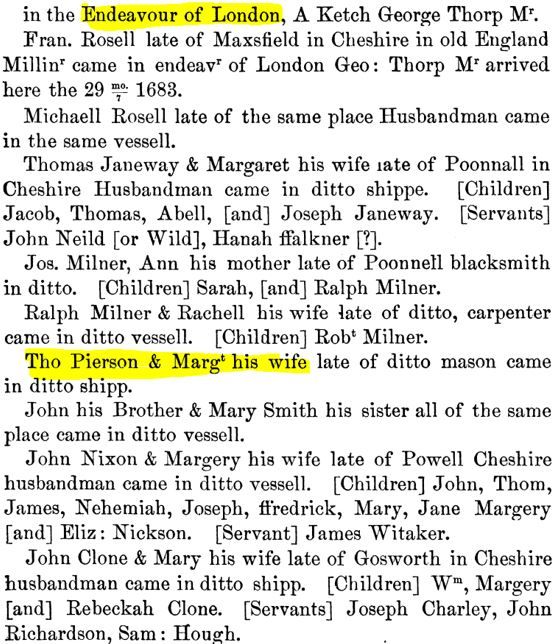

The next year in the summer of 1683 Thomas Pearson and his wife Margery sailed to America on the ship Endeavor. Thomas waited until 1683 because William Penn had to put into action his plan to create an American utopia for the Quakers.

Thomas and Margery Pearson to America

It has been over 335 years and 12 generations ago that Thomas Pearson set foot in America. The journey from England to Philadelphia was a long ocean crossing. With Thomas was his new bride, Margery Smith Pearson, who was 6 months pregnant when they landed. It could not have been a pleasant crossing for her! Her sister Mary Smith was her companion and Thomas’s brother John Pearson was on the same ship, The Endeavor that landed September 29th, 1683. The ship was out of Liverpool.

It is probable the ship was full of Quaker colonists. William Penn had obtained a large area of land the year before, and he opened it up to the Quakers. John Pearson inherited money from his father’s estate and likely used that money to buy land from William Penn the year earlier. What where the Pearsons leaving behind? Their parents were both dead and buried at Moberly, Cheshire England. They undoubtedly left many relatives. The Pierson/Pier name can be found in Cheshire for two centuries before. Travel from one place to another was not common or easy and gene pools received little new blood.

They left a country civilized for many centuries. While life would not be plush, especially by our standards, life in England was as good as it got except for the sufferings of the Quakers with the local magistrate. They left behind established farms and towns to clear the forest of America.

What did they find when they arrived? William Penn had received a large chunk of wilderness in America in March 1681. Two years after the purchase, it was still wild, with only a few small settlements huddling along the leading edges. The Quakers settlers found Philadelphia a sea of mud, very few decent houses, and many streets of tents and caves for shelter. The Quakers built Philadelphia from the ground up starting in 1682.

Pennsylvania provided a lure, though, and settles streamed in. People were willing to work, to build a new society from the ground up. They came by the boat load over the next several years from Europe. Though all of Penn’s political goal were not realized, his colony was overwhelming success from the numbers alone. By 1699 Philadelphia area was 50% Quakers with many prominent in public life. They were often faced with awkward challenges imposed by the King of taking oaths and military conflicts in which they wanted no part in. Until 1750s the legislature remained largely in Quaker hands. Then the independence movement came and Quaker’s refusal to fight was seen as supporting the status quo of England and the King oppressing the colonies provided the final blow that took Quakers out of public offices. By 1776, Philadelphia was the second largest city in the British Empire with only London being larger.

Fig 4.5 – Passenger list for Endeavor

Thomas Pearson in America

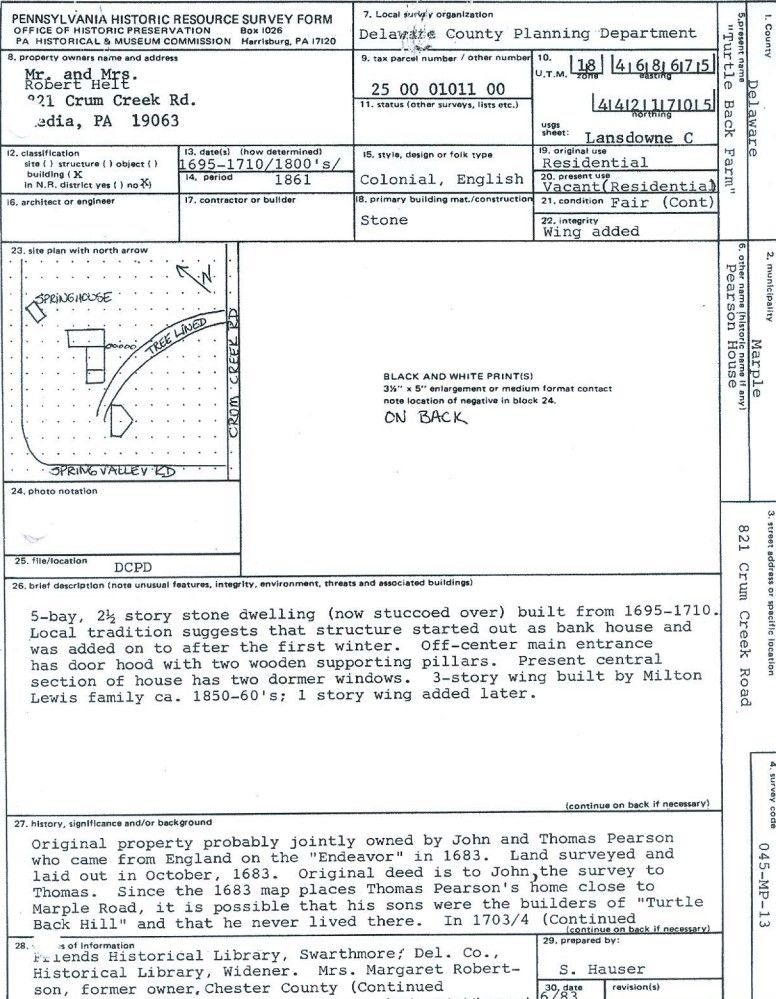

Thomas was accompanied his brother John, sister in-law Mary Smith and his new wife Margery to Pennsylvania on the Endeavor. Margery’s brother, Thomas Janney and his family also was on the same ship. Pearson’s grant of land was surveyed in Marple Township, October 25, 1683, where they proceeded at once to make their settlement. Thomas Pearson, and likewise his brother Edward Pearson, followed in the footsteps of their father Lawrence and of their uncle Robert Pearson learning the mason trade.

A year later, in 1684 at the Chester County Court, Thomas Pearson was made road supervisor as well as constable of Marple Township. On several occasions he served in the grand inquest (jury) of the court. In 1689, Thomas became tax collector for Marple, and in 1690, fence viewer. Duties of a fence viewer is upon request of any citizen, the fence viewer views fences to see that they are in good repair and in case of disputes between neighbors, works to resolve their differences. Problems such as size, condition, and distance from property lines are complaints that still arise between neighbors. In 1708, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly from Chester County. In 1703, and again in 1716, he was made overseer of Springfield meeting. He died in 1734 on the Marple homestead of his first settlement, and doubtless lies buried in the Springfield graveyard with his wife and others of his family in unmarked graves. Margery Pearson died in 1747 at the age of 89.

Margery, his wife, was the mother of ten children, all duly recorded in the meeting registers, her oldest child, Robert, having been born February 3, 1683, only but a few months after settlement in their new land. What type of living quarters did they have the first year after arriving? Their settlement was unimproved woodlands with absolutely no housing. They must have lived in tents through the winter until they could build their first home from wood, stones, sticks and clay.

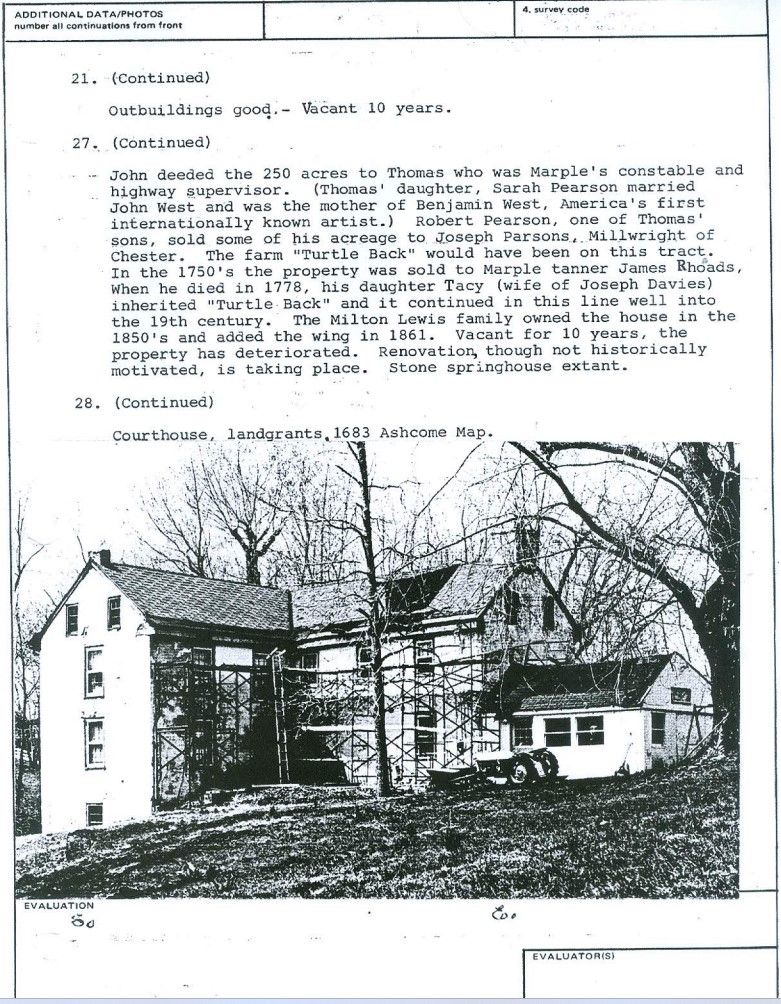

Fig 4.6 – Photo of Turtleback farm and the original homesite of emigrant Thomas Pearson

Fig 4.7 – Thomas Pearson and John Pearson settlements early 1700 map

Thomas Pearson bought additional land next to his farm after he settled his original 250 acres. He bought the following tracts of land in what was then Chester County, which is now in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Thomas first moved on to the land which his brother, John brought from William Penn in 1681. On December 29th, 1697, he bought 300 acres of land that adjoins the lot on which the Springfield meeting house stands. On February 28th, 1703, he bought another tract of 300 acres north of the second tract. Later Thomas and Margery deeded this tract to their oldest son Robert. On January 20th, 1723, he bought a tract of 50 acres lying between the first and second tracts. This made a farm of 900 acres. In 1731 they deeded to their oldest son Robert, 300 acres of land being a part of the first, second and fourth tracts of land which he bought.

Will Of Thomas Pearson

Proved 25 March 1734

I, Thomas Pearson of Marple in the County of Chester and Province of Pennsylvania being weak in body but of sound disposing mind and memory praises be given to Almighty God, do make and ordain this my Last Will and Testament in manner and form following, first and principally I command my Soul into the hands of Almighty God that gave it, and my body I commit to the earth to be decently buried at the discretion of my executors hereinafter named. And as touching all such temporal estate and worldly effects as it hath pleased the Lord to bless me with, I give and dispose thereof as follows:

Item. I will that all my just debts and funeral expenses be fully discharged and paid.

Item. I give and bequeath unto my son John Pearson the sum of fifteen Pounds current money of America due upon bond to be assigned over to him by my executors hereinafter named within six months after my decease.

Item. I give and bequeath unto my son in law John West and my daughter Sarah his wife ten pounds current money of America to be paid unto them by my Executors within two years after my decease.

Item. I give and bequeath unto my son in law Nicholas Rogers and my daughter Mary his wife the sum of fifteen pounds current money of America due upon bond to be assigned over by my executors within six months after my decease.

Item. I give and bequeath unto my son in law Peter Thompson and my daughter Margery his wife the sum of fifteen pounds current money of America due upon bond to be assigned over to them by my Executors within six months after my death. And whereas my son Robert Pearson by divers obligations and conditions to them is and Standeth bound unto me by virtue of them all, in the just and full sum of fifty pounds current money of America as aforesaid due and payable at the days and times in every of their limited and appointed relation thereunto had more fully appears, which said fifty pounds I give and dispose of in a manner following (viz) ten pounds part of thereof I give and bequeath unto my son John Pearson. Ten Pounds more thereof to my son in law John West and Sarah, his wife. Ten pounds more thereof to my son in law Nicholas Rogers and Mary his wife. Ten pounds more thereof to my son in Law Peter Thompson and Margery his wife. And Ten pounds residue or remainder thereof to my son Robert Pearson aforesaid to be paid to each and every of them by my executors in some convenient time after my decease.

Item. I give and bequeath unto my four sons namely, Robert Pearson, Lawrence Pearson, Enoch Pearson, and Abel Pearson, to each of them five shillings to be paid to them by my executors.

And all the rest and residue of my Estate Real and personal of what nature or kind soever, proved by any ways or means whatsoever to be my right property, claim or demand whether written or verbal agreement, I give and devise unto my dear and loving wife Margery Pearson to her proper use, behoof, benefit and disposal forever. And lastly, I do nominate, constitute, and ordain my trusty and well-beloved friends, Bartholomew Coppock of Marple and Samuel Levi, Junior. of Springfield in the County of Chester aforesaid to be my lawful Executors of this my last will and Testament reposing. Reposing in them Special Trust and Confidence in the fulfilling, accomplishing, and executing thereof in every part, according to the true intent and meaning of the same, which I do pronounce and declare to be my last

will and testament and none other revoking hereby all former will and wills by me made either verbal or written. In witness thereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal dated the sixteenth day of October in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and thirty. 1730

Thomas Pearson

Signed, sealed, and pronounced and declared by the above Thomas Pearson, the testator for and as his last will and Testament in the presence of us ye subscribers.

Rebeca Coppock, Sarah Coppock, Morda Massey.

Source: Book “The pearson family tree from England to America” [ages 85-89)

It is more interesting to convert the money in the will to USD in today’s dollars. Below are the conversions.

- To John Pearson the sum of fifteen Pounds = $2,835 in 2022

- My son in law John West and my daughter Sarah his wife ten pounds current money of America to be paid unto them by my Executors within two years after my decease. = $1890 in 2022

- I give and bequeath unto my son in Law Nicholas Rogers and my daughter Mary his wife the sum of fifteen pounds. = $2835 in 2022

- I give and bequeath unto my son in Law Peter Thompson and my daughter Margery his wife the sum of fifteen pounds = 2,835 in 2022

- Robert Pearson of fifty pounds current money - $9410 in 2022

- John Pearson ten pounds part. $1890 in 2022

- Ten Pounds more thereof to my son in Law John West and Sarah, his wife. =$1890 in 2022

- Ten pounds more thereof to my son in Law Nicholas Rogers and Mary his wife. $1890 in 2022

- Ten pounds more thereof to my son in Law Peter Thompson and Margery his wife. = $1890 in 2022

- I give and bequeath unto my four sons namely, Robert Pearson, Lawrence Pearson, Enoch Pearson, and Abel Pearson, to each of them five shillings = $50 in 2022

Fig 4.9 – Friends meeting house where Thomas Pearson and family attended and graveyard where he and many family members are buried in unmarked graves.

Chapter 5

Enoch Pearson (b1690)

Mary Smith (b1697)

Generation 4

Enoch Pearson was born in May 1690 at his family homestead in Marple township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. He was the 4th son of 10 children of Thomas and Margaret Pearson. He married Mary Smith on Dec 5, 1719, when he was 29 years old. Their marriage was without the approval of their parents or the consent of the Society of Friends Church. The following were their children with our ancestor in bold text: William, Rose, Benjamin, Samuel, Enoch jr., Thomas (1728), Mary, Elizabeth, Joseph, Sarah, Mary, and Margery.

To prevent being disowned by the church, Enoch wrote a formal apology which read:

January 22, 1720,

To the Chester Monthly Meeting of Friends

I have according to your desire made acknowledgement to my parents and to wife’s father for my offence in marrying contrary to the good order established amongst Friends for I gave way too much to my own will contrary to the leadings of the good Spirit of God, the which is in my mind to confess unto you, and also I am sorry for my outgoing and desire a reconciliation with you hoping my future conduct may be more honorable. I also desire your prayers that my faith fail not.

(Signed) Enoch Pierson

Enoch official marriage on December 5th, 1719, was after their first son William Pearson was born November 9th, 1718. Enoch and Mary’s second child, Margery was born a year after their marriage in December 1720. In total they had ten children plus two that died as infants. Four of their younger children were born in the new Quaker settlement in Virginia.

In 1734, Thomas Pearson (father of Enoch) died. In his father’s will, Robert Pearson, being the oldest son, inherited the bulk of the estate including over 50 pounds (about $10,000). Other children received between 10 and 25 pounds ($2,000- $5,000). Enoch was left out of most of the estate and received only 5 shillings ($50) from his father.

The Hopewell monthly meeting house near Winchester, Virginia was established in 1734. Soon after his father’s death, Enoch, and Mary at the age 44 moved their family 230 miles southwest to Frederick County, Virginia in the to help in the establishment of this new meeting house in the Shenandoah Valley. They had six children and two others who died as infants. Thomas (Tommy) Pearson my ancestor was born in Pennsylvania. Four more children were born to them in Virginia.

Enoch Pearson family moves to Virginia

During the quarter of the Century between 1725 and 1750, many Pennsylvania families moved first Southwest and then Southward, along the edge of the Appalachians and into the fertile valleys of the Eastern hills. These were chiefly Quakers, Pennsylvania Dutch, and Scotch-Irish. Members of all three groups settled in the Shenandoah Valley, and in other Western parts of Virginia, in Western North and South Carolina, and a few in Georgia, along the upper part of the Savannah River. The movement progressed Southward, striking Georgia about 1780. These people left Pennsylvania because that colony had begun to fill up, and land became more expensive. In the country to which they moved lay fertile, unclaimed land, which was easily turned into productive farms. Although Quakers were opposed in principle to the institution of slavery, many of the southern members bought and owned slaves, although they seldom sold them.

Among the early meetings set up in Virginia were Hopewell, in Frederick County, Virginia. Enoch went with 70 Quaker families to set up a new settlement. The farms in the Shenandoah valley were virgin soil and inexpensive compared to farms around Philadelphia at the time.

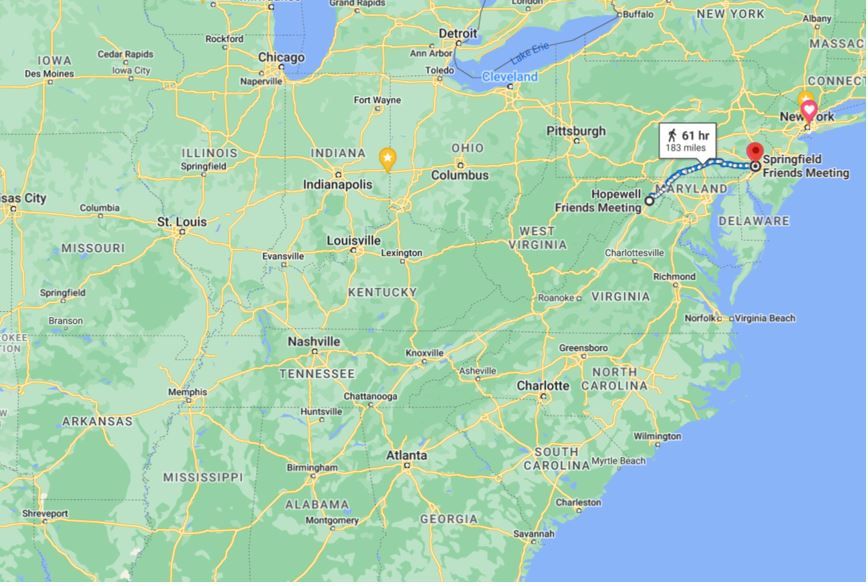

Figure 5.1 – First movement for the Quaker Pearson’s were Enoch in 1734 was from Springfield Friends to Hopewell Friends Meeting.

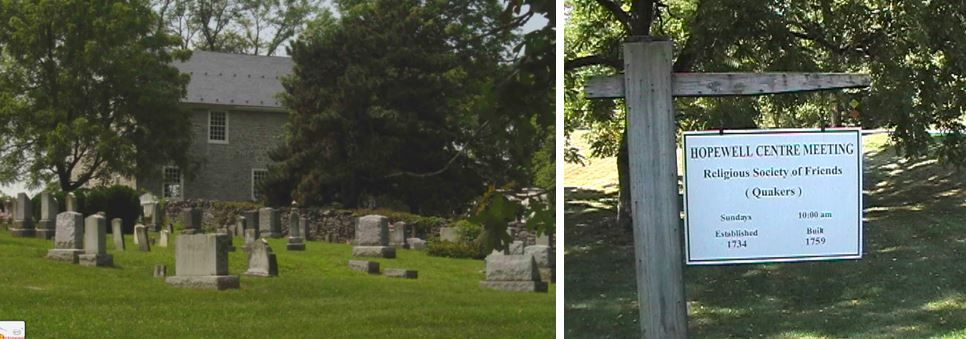

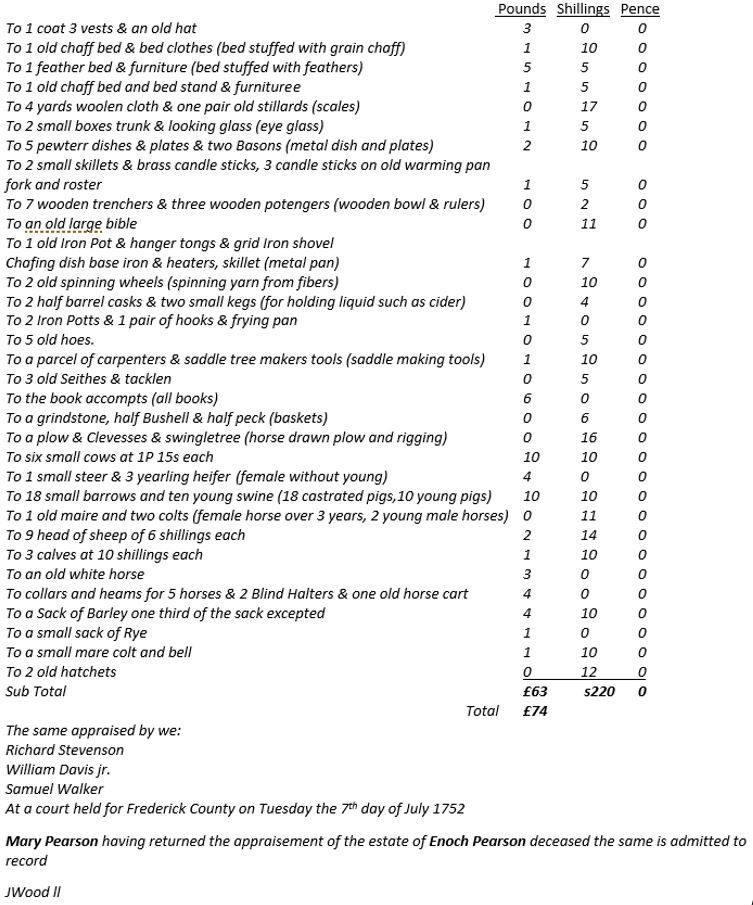

Enoch Pearson lived in Virginia for 15 years as a farmer and died on February 23, 1749, at age 59, without leaving a will. He is buried at the Hopewell Meeting House graveyard, 6 miles north of Winchester, Virginia.

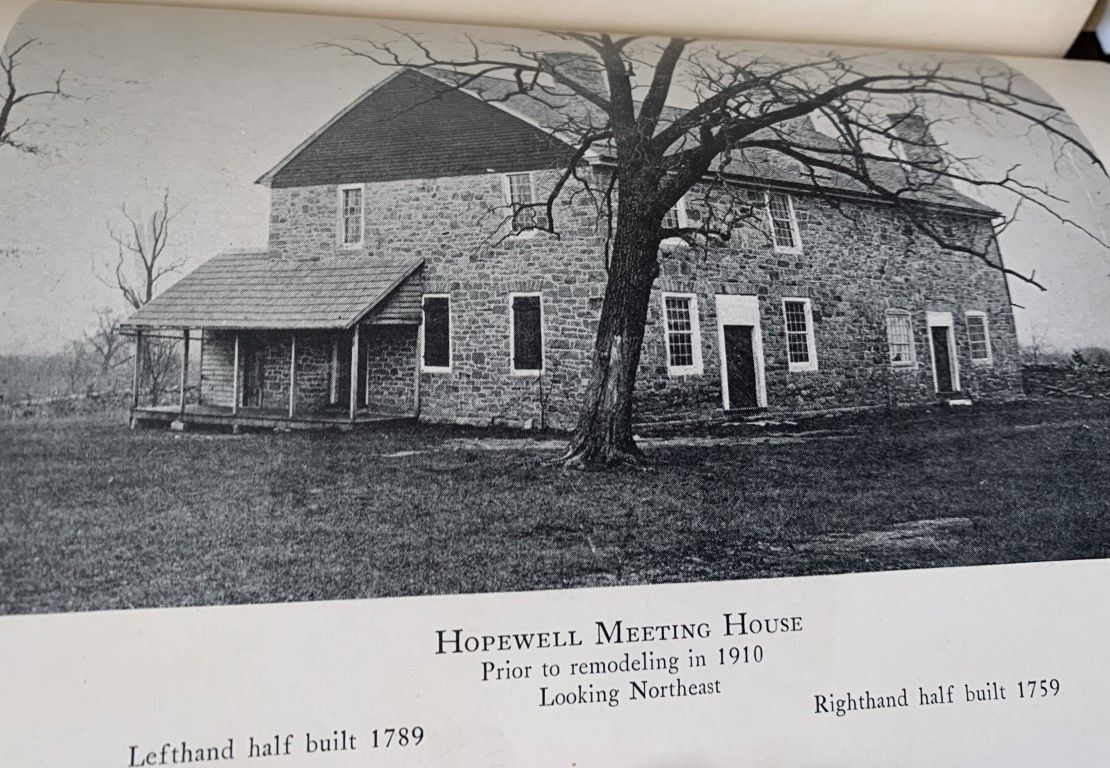

Fig 5.2- Hopewell Meeting house graveyard where Enoch Pearson is buried

In the court records of Frederick County, Virginia, we find where Mary, applied for administration papers for his estate and was granted on August 9th, 1749.

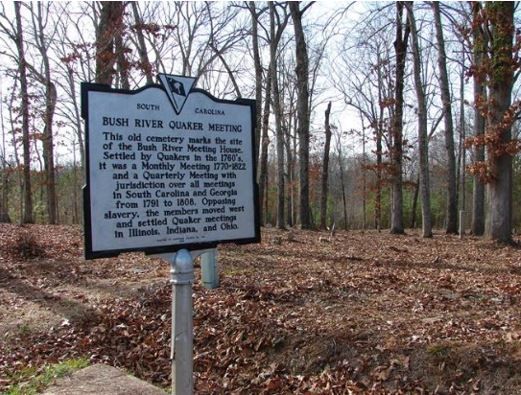

The records of Chester County, Pennsylvania and Frederick County, Virginia, do not show that Enoch owned real estate. However, in a deed executed by his parents in 1731 noted: thence north thirty-three degrees westerly by the land of Enoch Pearson. This land held by Enoch was part of his father’s 900-acre farm. After Enoch’s death Mary Pearson moved with her son Samuel to the Bush River settlement in South Carolina in 1771. She is my only direct ancestor that is buried in South Carolina at the Bush River Quaker Cemetery in 1780.

Chapter 6

Thomas Pearson (b1728)

Ann Powel (1729)

Generation 5

Thomas (Tommy) Pearson was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania on March 24th, 1728, to Enoch and Mary Pearson and was the grandchild of Thomas Pearson who emigrated from England. Thomas was the fourth son of Enoch and Mary and was only 5 years old when he and his family moved to Frederick County, Virginia to a new Quaker settlement in the Shenandoah Valley. Tommy’s father died when he was 20 years old, and he moved back to Pennsylvania. He married Ann Powell on June 5th, 1751, in Philadelphia. The marriage was by a swede minister, whose certificate of the fact is still preserved in Thomas Pearson’s old bible. In 1768 Tommy and his wife decided to move to Newberry, South Carolina where new land was opening in a new Quaker community. They waited a couple of years after buying land in South Carolina before they made the big move in 1770, right before the revolutionary war. Six of their children were already born in Pennsylvania and the last two would come in in South Carolina. Unfortunately, Ann died from complications of childbirth of 8th child, Jonas, on October 27th, 1773, 6 weeks after birth. Thomas Pearson was a blacksmith, saddler, and harness maker, as well as a farmer. He was known as “Little Old Tommy” because of the great age he achieved.

Tommy received a grant for 300 acres on the Broad River in South Carolina on December 29th, 1767, however, didn’t move his family there until 1770. Land grants were used in colonial times to encourage immigration and investments in the new colonies. Grants would be given according to family size and the grantees’ ability to cultivate the land. The number of acres in a homestead grant was determined by the size of the grantee’s family, including servants. Fifty acres became the normal headright. His widowed mother Mary and all his brothers and sisters also moved in the same timeframe setting up their own farms.

Tommy later received another grant for 100 acres in Berkeley County, South Caroline on February 10, 1773. After Ann’s death in 1773 in South Carolina, Tommy married Mary Campbell on July 8, 1775, at Padgett’s Creek Monthly Meeting, South Carolina. She also was a widow and had three children in tow and went on to have two more with Tommy, Rebecca b1776 and Mary b1778. Both born at Bush River, Newberry County, South Carolina.

American Revolutionary War

The French and Native American War ends after France surrenders all its American lands east of the Mississippi to Britain in 1763. The cost of the war and maintaining an army lead the British to impose new taxes on its colonist, with world-shaking results. Clashes between British troops in Boston over taxes lead to what was called the Boston Massacre in 1765. In the next 10 years growing tensions was building on the taxes leveled on all types of imports and the War of Independence breaks out for the next 5 years between the British and the American colonists.

Philadelphia was the largest city in North America at the time and the spiritual heart of the revolutionary America. Tommy and his young family lived in Philadelphia until 1769 and was in the middle of the tension that was building up before the war. Many Quakers began to criticize the increased British taxation under the newly passed Stamp Act however Quaker political leadership largely kept the protest nonviolent. The relative peace disappeared in 1767 with the passage of the Townsend Acts and by mid-1768 the Quakers leadership were unable to contain the swell of anti-British sentiments. The Friends were losing political support to more radical factions without reservation towards violence. Being Quakers, they had no desire to fight in any conflict. The Quakers opposed such activities as the declaration of American independence, which led to the Revolutionary War from 1775-1781, because they believed that “governments were divinely instituted and that they should only rebel should the government disobey the laws of God.”

This is the same time Tommy and his family purchased 300 acres on the Broad River in South Carolina. Tommy was a saddle and harness maker in Philadelphia at the time, however at the age of 41 he decided to leave Philadelphia and move to South Carolina to be a farmer. Could Tommy see the discontent of the colonist leading to violence and even war is not known, however he uprooted his family in 1769 before the Revolutionary War to go south. Eight years later Philadelphia fell to the British army.

There was a strong Britain loyalist support in the South and the strategy Britain initially had been to take advantage of the of strong loyalist support by beginning with a military drive from Charleston, South Carolina and perhaps sweep through the Upcountry where Tommy lived while gathering loyalist men to take on General Washington in the North. However, the battle of Sullivan’s Island on June 28, 1776, and the win from the Patriot Continental Army made Britton rethink its strategy and they left the South for 3 years during the war. In 1780 the British returned to South Carolina and landed a major force near Charleston, South Carolina establishing control over the southern coast. The British navy didn’t have any need for the pacifist Quakers and pretty much left the Quakers alone at their farms in Newberry, SC.

During the Revolutionary War, as legend goes, Tommy was captured by the British, who tried to impress him into service as a blacksmith. However, he exercised Quaker passive resistance, and refused to work. Some people have joined the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) based on his “patriotic service”, however, the documents to support the claim are in error. They claim military serviced in North Carolina, not South, and trace through a nephew, not son.

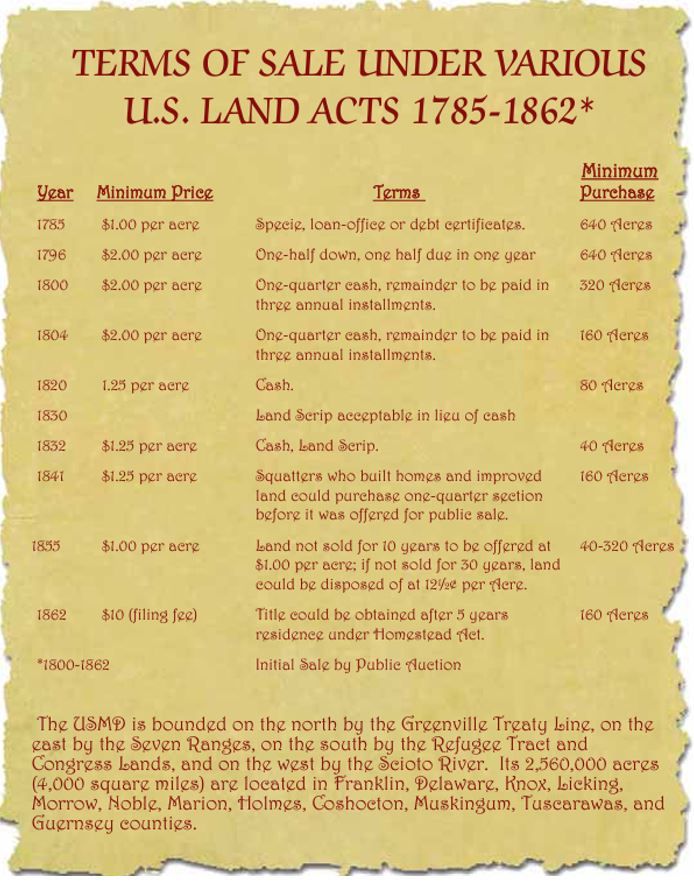

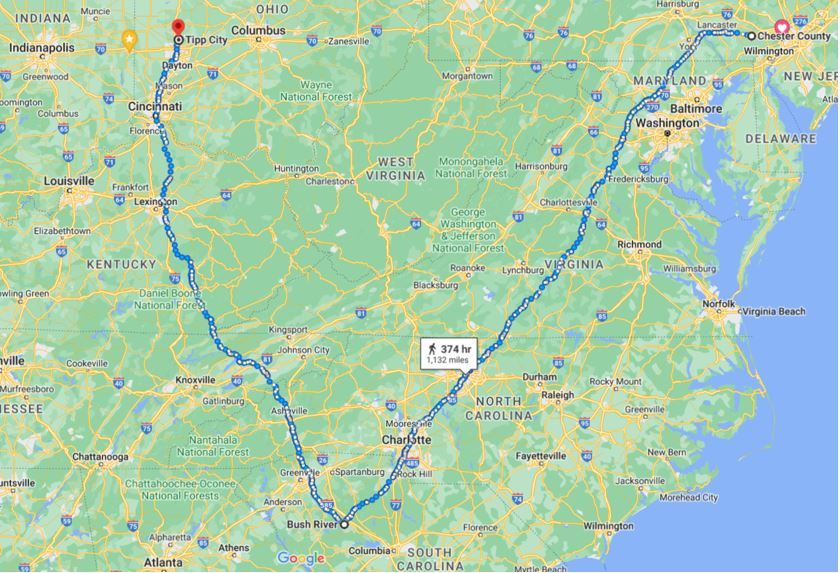

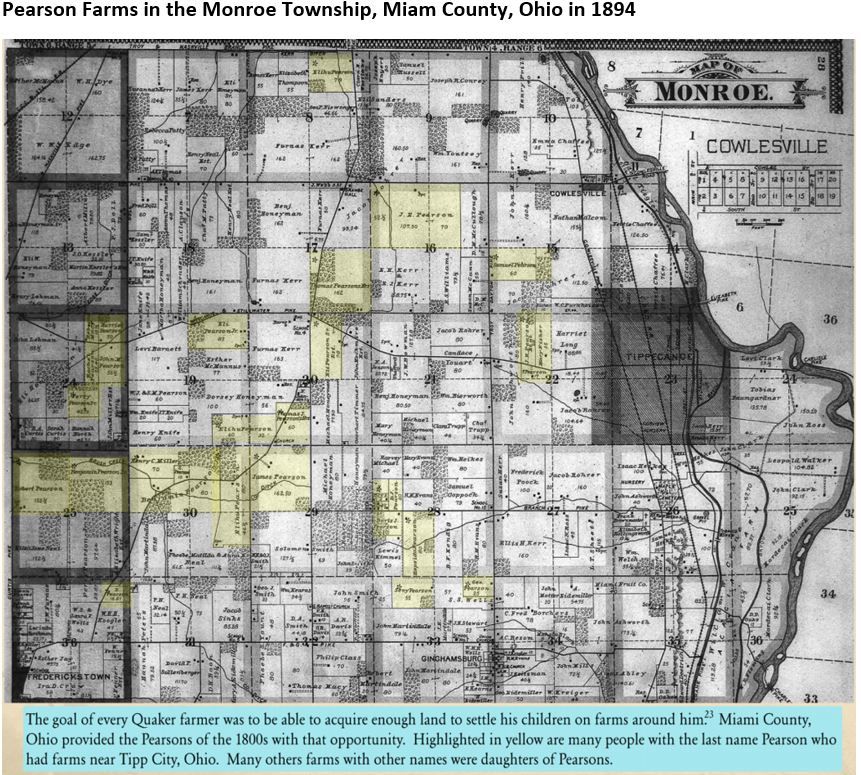

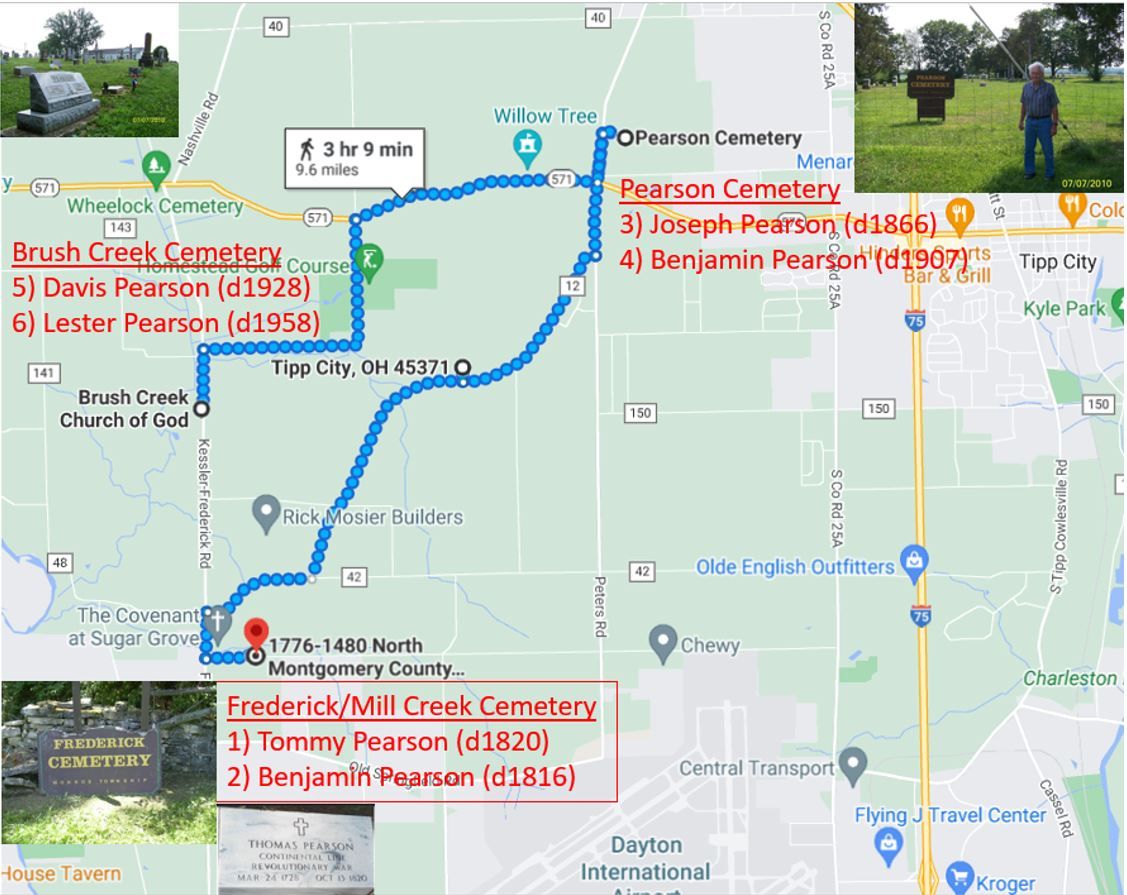

Tommy Pearson’s family migration to Miami County, Ohio

Tommy Pearson the grandchild of Thomas Pearson (b1653) who emigrated from England, moved his family from Pennsylvania to farmland he bought near Bush River, South Carolina. South Carolina was starting a new Quaker settlement with fine land to farm and his family quickly grew into the community. A few years after arriving his wife Ann died after her eighth child was born. Two years later Tommy remarried, had 2 more children, and lived in the Bush River area for another 30 years from 1775-1806. Between 1803-1806, he and his son Benjamin Pearson and many of this family moved to the Miami Valley, Ohio area where a new wilderness could be cleared and turned into rich farmland. The land was acquired from the Native Americans after the Treaty of Greenville through the Land Act of 1804 where it made it easier to purchase federal lands with a minimum of 160 acres at $2 an acre through installment loans ($47 an acre in 2022). As the frontier opened the Pearson’s flourished in the Ohio area mostly as farmers for the next 7 generations.

Bush River, South Carolina Quakers

What became of the Friends in South Carolina? Between 1800 and 1804, a celebrated Quaker preacher, Zachary Dicks, passed through South Carolina. He was thought to also have the gift of prophecy. The massacres of Haiti in 1804 was fresh where soldiers who were mostly former slaves moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families. Even whites who had been friendly and sympathetic to the black population where killed. Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed. He warned Friends to come out from slavery. He told them if they did not their fate would be that of the slaughtered Islanders. This produced in a short time a panic, and removals to Ohio commenced, and by 1807 the Quaker settlement had, in a great degree, changed in population. Land which could often since, and even now after near forty years cultivation in cotton, can be sold for $10, $15, and $20 ($370 in 2014) per acre, was sold then for $3 to $6 ($111 in 2014). Newberry thus lost, from foolish panic and superstitious fear of an institution, which never harmed them or any other body of people. Avery valuable portion of its white population.

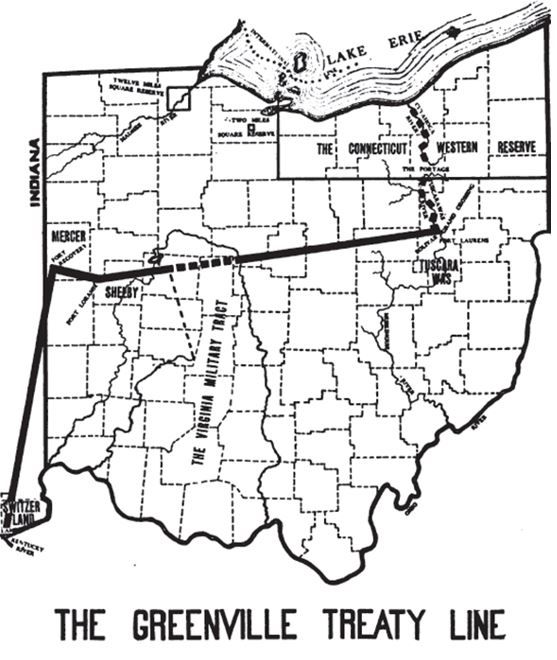

Greenville Treaty Line

At Fort Recovery, Ohio in Mercer County, the original surveyor’s stake was found which marked the western terminus of the part of the Greenville Treaty line running from Fort Laurens in the eastern part of the state to Fort Recovery. From this point the line ran southwesterly to a point on the Ohio River opposite the mouth of the Kentucky River. By the terms of the treaty. Signed on August 3, 1795, the Native American tribes gave up their claims to the lands south and east of this line. Current cities that are east of the line included Richmond, Liberty, and Brookville, Indiana. These areas were part of the “Indian Territory” shown in figure 6.2 and not conceded until after the War of 1812 with the British.

Fig – 6.1 Greenville treaty line 1795 – All areas south and east of line were United States Territory

Fig – 6.2 United States map in 1800

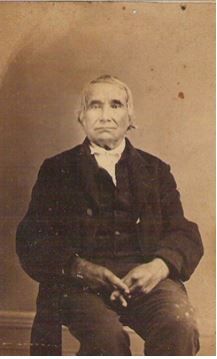

The Story of “Old Tommy”

“I will now give an account of some of the most prominent persons who came from Newberry and settled in the tree counties previously mentioned. Many of those emigrants being unknown for forgotten by the author of the Annals of Newberry, are not mentioned by him, and we need not wonder, for he was a boy at the time of their emigration. The traits of some, however, are given with almost surprising accuracy: and could he have known their subsequent lives it would no doubt have given him much satisfaction and would have been a supplement to the Annals.

The first I’ll mention is Thomas Pearson, “Little Old Tommy.” Who lived to the greatest age of any who came from Newberry, besides being the oldest emigrant to his township, and, as near as I can learn, country? Born in 1728, he was older than the Father of his Country, a fact which seemed to attach additional importance to him. In early life he lived in Philadelphia, following the trade of saddler and harness-maker.

Years before, and during the Revolution, he and his family resided in Newberry District and had their full share of its honors. Once, when a captive, his enemies required his serviced in saddlery and harness work, regardless of his lack of tools. He answered them by say in that ‘Neither wise men nor fools can work without tools’ the piquancy of which caused them to laugh and excuse him. He appears to have occupied the first seat in the ‘common Meetings’ of Friends.

A granddaughter of his told me that once during the solemn quiet of a meeting a partially insane woman come in with fruit in her apron and going up to him said, ‘Here, Mr. Pearson, I’ll give you the apples if you preach today” Being a harmless person they got rid of here in a quiet way, but whether or not the regarded her interruption as a rebuke upon their silent worship I was not informed. I think it was in 1805 or 1806, that Father Pearson left Newberry with a numerous retinue of children, grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Coming directly to Miami County they pitched their tents in proximity to the Jays and Jenkins, who had preceded them. It was not many years before his many descendants were settled comfortably around him and he saw teeming fields, in place of dark, tangled forests.

His wife died, and though in advanced age, he took another. A few years more and his walk became tremulous, his eyes grew dim, and his hearing blunted. The writer saw him in 1820, when he had Old Dodson’s Three Warnings – He was lame, and deaf, and blind. He would walk only with support on both sides, could hear only by loud speaking in his ear, both day and night were alike to him. In this lamentable condition we may well suppose time hung heavy on his hands. Upon asking what time it was, if answered tone o’clock, he would say and repeat, ‘Ten o’clock, ten o’clock,’ striving, but in vain, to impress it upon his memory, for it would not be long before he repeated the question. The author, child as he was, pitied him striving, whose lamp of life, so nearly gone out, seemed to be leaving him rather impatient. How much the weight of blood upon his soul distressed Napoleon, we cannot know, but we do know he had his sight and hearing, which old Thomas Pearson had not. In natural ability they bear no comparison, neither did they in ambition. The first died in the calmness and quiet of Christian resignation, the second a few months after with his spirit deliriously engaged in the strife of battle and the rage of tempest around him.